Hospitals that do not have neurosurgical coverage are faced with a dilemma when they receive a head-injured patient. Do they automatically transfer to a higher level trauma center, or do they keep the patient? This is especially poignant in rural areas, where transfer times may be lengthy. If a patient doesn’t really have any significant pathology, they are likely to be evaluated at the receiving Level I or II center, then discharged all the way back home. But if they are kept at the initial hospital, there may be a nagging doubt about what happens if…

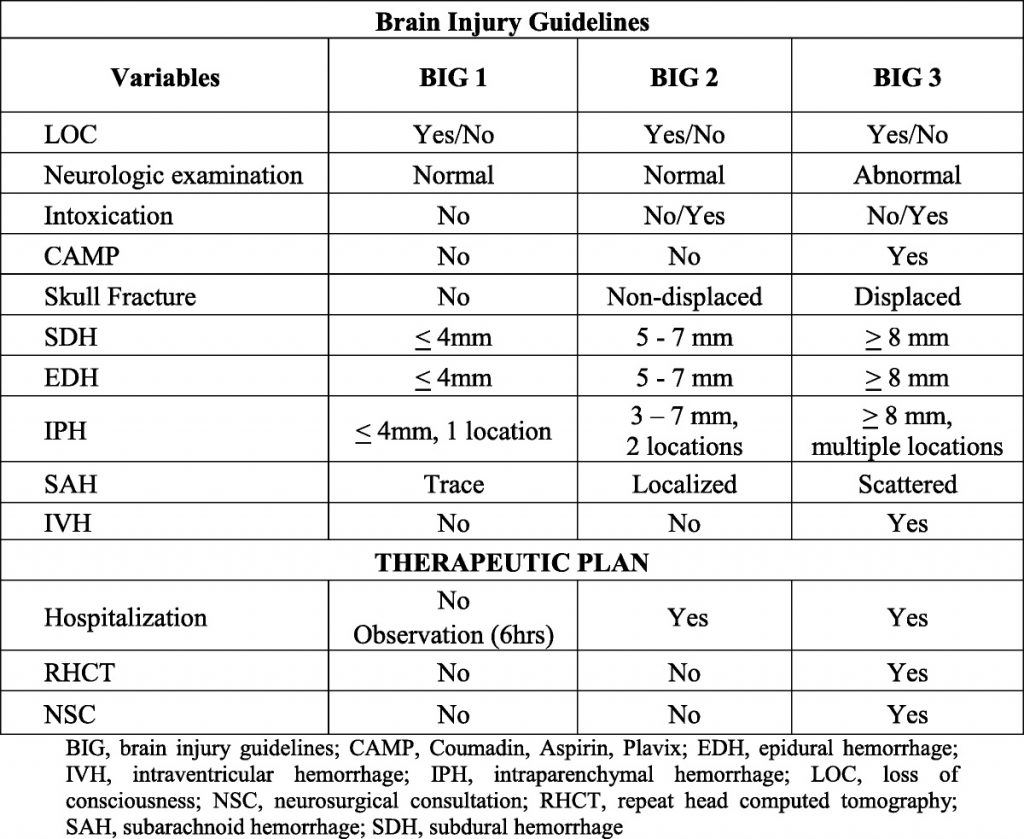

Five years ago, the group at University of Arizona – Tucson published a simple brain injury classification system that was designed to predict which injuries were likely to progress and need neurosurgical intervention. They called this system BIG for Brain Injury Guidelines. It was created and validated on a group of nearly 4,000 patients over four years, and the results have been promising. Since then, BIG has been validated using small study groups (<405) in pediatric head injury, and at Level I and III trauma centers.

Here’s the guideline:

One of the Quick Shot presentations at next week’s EAST Annual Scientific Assembly is another validation study at a Level III center in Lake Havasu City, Arizona that introduces one small modification to the guidelines. Normally, BIG is calculated after CT of the head is complete. This modification entailed BIG calculation after anticoagulation was reversed. Patients with BIG scores of 1 or two after reversal was complete were kept at the Level III, and were managed by the trauma surgeons. All BIG 3 patients were transferred to a higher level center.

Four years of trauma registry data were analyzed. During the first two years, patients with any positive BIG score were transferred. During the final two years, only patients who scored BIG 3 after reversal were moved.

Here are the factoids:

- During the pre-BIG period, there were 72 transfers: 36 BIG-1, 23 BIG-2, and 13 BIG-3

- Once the protocol was in place, there were 119 patients identified, 52 patients with BIG-1 or 2 who were kept and 67 BIG-3 patients who were transferred

- 13 patients in the post-BIG time frame were excluded

- None of the BIG-1 or 2 patients required transfer later

- 39 of the 52 BIG-1 or 2 patients had repeat scans, and none worsened clinically, with an average hospital length of stay of 1.4 days

- Estimated helicopter transport savings was $1.9M based on an average charge of nearly $50K per flight

The authors concluded that modified BIG could be used to triage neurotrauma patients for transfer, but cautioned that good clinical judgment should also be applied.

Here are some questions for the authors and presenter to consider in advance to help them prepare for audience questions:

- Are you satisfied that BIG is sufficiently validated? To date, there are only a handful of validation studies and they have relatively small numbers.

- Why did you choose to modify the score to wait until anticoagulation? Couldn’t this nullify the validation studies?

- Do you have any practice guidelines in place to ensure consistent care of the patients you now keep at your center? Do they allow you to manage common problems like subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraparenchymal hemorrhage?

- How did you ensure that your surgeons, hospitalists, and nurses were comfortable managing these neurotrauma patients? Did you have any educational sessions or other training for things like GCS monitoring and neuro exam?

- How do you reverse anticoagulation, and how long does that usually take? Plasma and prothrombin complex concentrate are commonly used, but with vastly different reversal times. And what do you do about aspirin, clopidogrel, and the novel oral anticoagulants?

- Why did you exclude 13 patients once you started using BIG?

- Has your hospital administration provided any numbers regarding increased revenue from this practice? Your hospital is larger (171 beds), but this type of information will be vital for small, critical access hospitals.

This is very interesting work, and highly applicable to rural trauma centers!

References:

- Successful management of select radiographic intracranial injuries in a rural trauma center without neurosurgeon coverage using a modified brain injury guideline. EAST 2019, Quick Shot Paper #6.

- The BIG (brain injury guidelines) project: Defining the management of traumatic brain injury by acute care surgeons. J Trauma 76(4):965-969, 2014.