A reader requested that I write about post-embolization syndrome. Not being an oncologist or oncologic surgeon, I honestly had never heard about this before, let alone in trauma care. So I figured I would read up and share. And fortunately it was easy; there’s all of one paper about it in the trauma literature.

Post-embolization syndrome is a constellation of symptoms including pain, fever, nausea, and ileus that occurs after angio-embolization of the liver or spleen. There are reports that it is a common occurrence (60-80%) in patients being treated for cancer, and there are a few papers describing it in patients with splenic aneurysm. But only one for trauma.

Children’s Hospital of Boston / Harvard Medical School retrospectively reviewed 12 years of their pediatric trauma registry data. For every child with a spleen injury who underwent angio-embolization, they matched four others with the same grade of injury who did not. A total of 448 children with blunt splenic injury were identified, and (thankfully) only 11 underwent angio-embolization. Nine had ongoing bleeding despite resuscitation, and two had developed splenic pseudoaneursyms.

Here are the factoids:

- More of the children who underwent embolization had extravasation seen initially and required more blood products. They also had longer ICU (3 vs 1 day) and hospital stays (8 vs 5 days). Not surprising, as that is why they had the procedure.

- 90% of embolized kids had an ileus vs 2% of those not embolized, and they took longer to resume regular diet (5 vs 2 days)

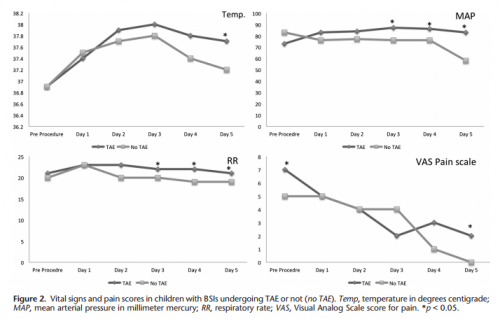

- Respiratory rate and blood pressure were higher on days 3 and 4 in the embolized group, as was the temperature on day 5 (? see below)

- Pain was higher on day 5 in the embolized group (? see below again)

Bottom line: Sorry, but I’m not convinced. Yes, I have observed increased pain and temperature elevations in patients who have been embolized. Some have also had an ileus, but it’s difficult to say if that’s from the procedure or other injuries. And this very small series just doesn’t have enough power to convince me of any clinically significant differences in injured children.

Look at the results above. “Significant” differences were only identified on a few select days, but not on the same days across charts. And although the authors may have demonstrated statistical differences, are they clinically relevant? Is a respiratory rate of 22 different from 18? A temp of 37.8 vs 37.2? I don’t think so. And length of stay does not reveal anything because the time in the ICU or hospital is completely dependent on the whims of the surgeon.

I agree that post-embolization syndrome exists in cancer patients. But the findings in trauma patients are too nondescript. They just don’t stand out well enough on their own for me to consider them a real syndrome. As a trauma professional, be aware that your patient probably will experience more pain over the affected organ for a few days, and they will be slow to resume their diet. But other than supportive care and patience, nothing special need be done.

Related posts:

- Solid organ injury tips

- Contrast blush in children

- Bedrest after pediatric solid organ injury? Really?

Reference: Transarterial embolization in children with blunt splenic injury

results in postembolization syndrome: A matched

case-control study. J Trauma 73(6):1558-1563, 2012.