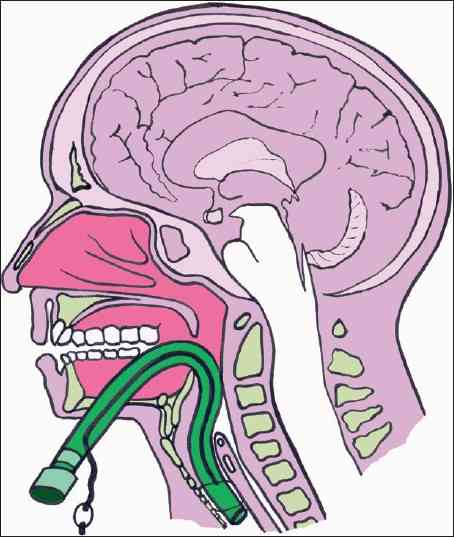

Centers that take care of blunt trauma are familiar with the spectrum of injury that is directly attributable to seat belt use. Although proper restraint significantly decreases mortality and serious head injury, seat belts can cause visceral injury, especially to small bowel.

Lap belt use has been associated with Chance fracture (flexion distraction injury to the lumbar spine) since 1982. The association between seat belts and intra-abdominal injury, especially with an obvious “seat belt sign” was first described in 1987.

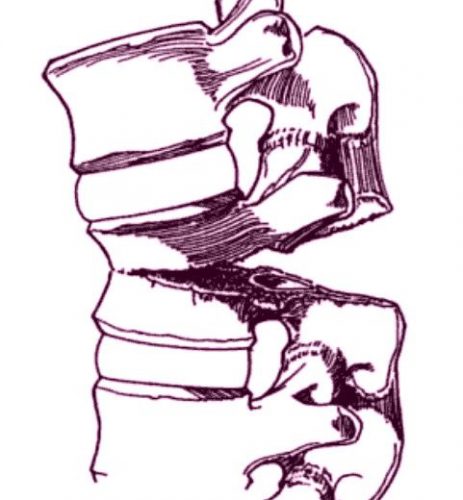

Chance fracture. The vertebra appears to split in half from posterior to anterior.

Twenty years ago, orthopedic surgeons in Manitoba finally put two and two together and reported a series of 7 cases of Chance fractures. They noted that 6 of the fractures were associated with restraint use. Seat belt sign was also present in 5 of the 6 patients with fractures and three of the six had bowel injuries.

The authors noted that many provinces were mandating seatbelt use at the time, and they predicted that the number of Chance fractures, seat belt signs and hollow viscus injuries would increase. On the positive side, the number of deaths and serious head injuries would be expected to decline.

Although this was a small series, it finally cemented the unusual Chance fracture, seat belt sign, and bowel injury after motor vehicle trauma.

Thankfully, three point restraints (lap belt + shoulder harness) has been required in the seats next to doors for a long time. And since 2007, they have been mandated in the middle seat as well. Thus, these injuries seldom occur in any but the oldest (beater) cars on the road. They are seen more frequently now with sports and extreme sports injuries.

Chance fractures are frequently unstable, involving all three columns of the spine. The anterior column fails under compression, and the middle and posterior columns fail from the distraction mechanism. Usually, this fracture pattern requires operative fixation. However, if the posterior column is intact, a TLSO brace can be tried. This fracture is at risk for non-union and development of kyphosis or a flat back, which can lead to chronic pain and an abnormal posture.

Reference: Pediatric Chance Fractures: Association with Intra-abdominal Injuries and Seatbelt Use. Reid et al. J Trauma 30(4) 384-91, 1990.