Yesterday, I wrote about an unusual way to use the Foley urinary catheter to plug a heart wound. This allows you to buy time to get to the operating room to perform the definitive repair. But this cheap and effective tool is very versatile, and can be used in other body areas as well.

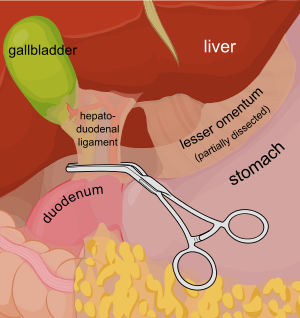

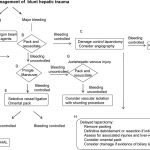

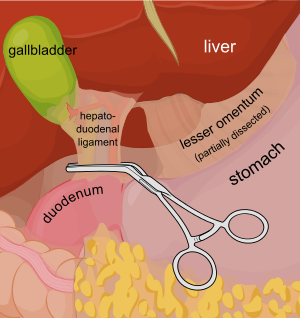

Consider a deep penetrating injury to the liver. It takes time to determine which method for slowing/stopping the bleeding is most appropriate. Sure, the doctor books say to occlude the inflow by gently clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament (Pringle maneuver). But this takes time, and can be difficult if there is lots of bleeding.

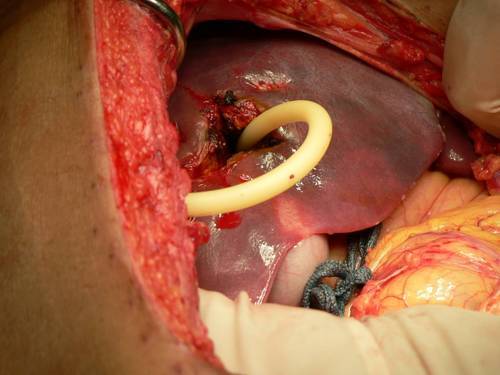

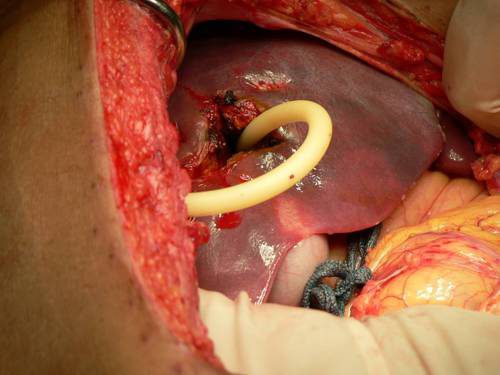

You may be able to gain some time by placing a properly sized Foley catheter directly into the wound and carefully inflating with saline. You must inflate the balloon to feel, not to its full volume. It should be snug, but not so full that it cracks the liver parenchyma and causes yet more bleeding.

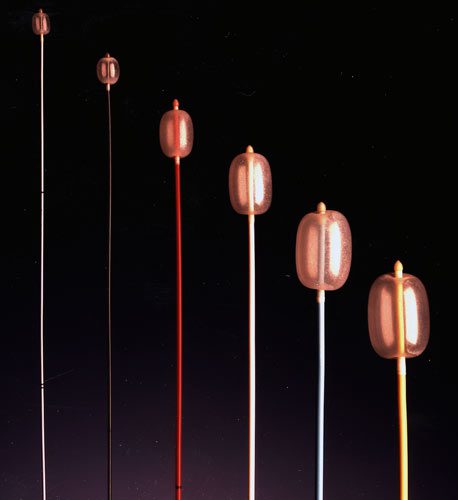

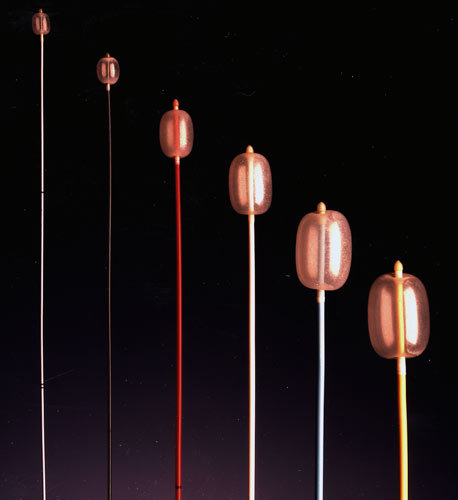

Bottom line: Any time you find yourself facing bleeding from hard to expose places, think about using a balloon catheter like the Foley. Sizing is critical, and the balloon volume is more important than the catheter diameter. Estimate the size of the area that needs to be occluded, and then ask for a catheter with a 10cc or 30cc balloon. If you need smaller, more precise control, try a Fogarty arterial embolectomy catheter instead.

As with the cardiac Foley, be sure to occlude the end so you don’t create a conduit for the blood to escape. If your patient does well, and you need to leave the catheter in place for a damage control closure, LEAVE THE CATHETER COMPLETELY WITHIN THE ABDOMEN. If you exteriorize the end, some well-meaning person may unclamp it, drop the balloon, or decide that it can be used for tube feedings.

TIP: If the distance between the balloon and the catheter tip is too long, DO NOT TRY TO SHORTEN THE TIP BY CUTTING IT! This will damage the balloon and it will not inflate.

Fogarty catheters