Tourniquets for extremity bleeding are definitely back in vogue. Our military experience over the past 20 years has shown us what a life saver this simple tool can be. It’s now carried by many prehospital trauma professionals for use in the civilian population. But what about bleeding from the nether regions? You know what I’m talking about, the so-called junctional zones. Those are the areas that are too proximal (or too dangerous) to put on a tourniquet, like the groin, perineum, axilla, and neck.

Traditionally, junctional zone injury could only be treated in the field with direct pressure, clamps, or in some cases a balloon (think 30Fr Foley catheter inserted and blown up as large as possible, see link below). In the old days, we could try blowing up the MAST trousers to try to get a little control, but those are getting hard to find.

An Alabama company (Compression Works) developed a very novel concept to try to help, the Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet (AAJT). Think of it as a pelvic compression device that you purposely apply too high.

Note the cool warning sticker at the bottom of the device!

The developers performed a small trial on 16 volunteer soldiers after doing a preliminary test on themselves (!). The device was placed around the abdomen, above the pelvis, and inflated to a maximum of 250 torr. Here are the factoids:

- All subjects tolerated the device, and no complications occurred

- Flow through the common femoral artery stopped in 15 of the 16 subjects

- The subject in whom it did not work exceeded the BMI and abdominal girth parameters of the device

- Average pain score after application was 6-7 (i.e. hurts like hell!)

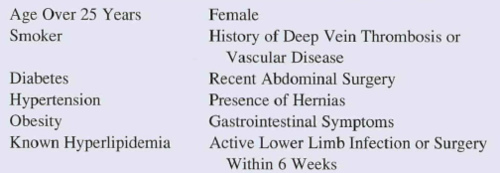

Here’s a list of the criteria that preclude use of this device:

Bottom line: This would seem to be a very useful device for controlling hemorrhage from pesky areas below the waist.

BUT! Realistically, it will enjoy only limited use in the civilian population for now. Take a closer look at the exclusion criteria above. Half of the population is ineligible right off the bat (women). And among civilians, more than a third are obese in the US. Toss in a smattering of the other criteria, and the unlikelihood of penetrating trauma to that area in civilians, it won’t make financial sense for your average prehospital agency to carry it. Maybe in high violence urban areas, but not anywhere else.

The company has received approval for use in pelvic and axillary hemorrhage control, so we’ll see how it works when more and larger studies are released (on more and larger people).

Related post:

Reference: The evaluation of an abdominal aortic tourniquet for the control of pelvic and lower abdominal hemorrhage. Military Med 178(11):1196-1201, 2013.

Thanks to David Beversluis for bringing this product to my attention. I have no financial interest in Compression Works.