I love to hate dogma. And there’s probably nothing in surgery more sacred and more ingrained than how to take care of a wound. Everybody knows that you have to keep surgical or traumatic wounds dry, and that once you can get them wet, showers are good at baths are bad. Right?

And for something as common as wound management, there must be some kind of research, right? Not so! I did quite a bit of digging through the literature since 1966 and managed to find only five papers. Here are the highlights:

- A prospective study of 100 patients were randomized to shower or bathe postoperatively. Of note, the wounds were sprayed with a clear plastic dressing before getting in the water. The was no difference in infection rates.

- Another prospective study of 100 patients with stapled incisions after spine surgery were allowed to bathe after 2 to 5 days. Compared to historical controls, there were no differences in infection rates even though the study patients had more complex operations than controls.

- A prospective randomized study of 121 patients after hernia surgery found no difference in infection between shower and dry groups

- A large randomized study of 817 patients similarly showed no difference between shower and dry groups

- Another randomized trial of 170 patients showed no difference in infections between shower after 24 hours and control groups

Get the picture? And interestingly, the few wound infections documented in any of the studies tended to occur in the dry groups, although this was not statistically significant.

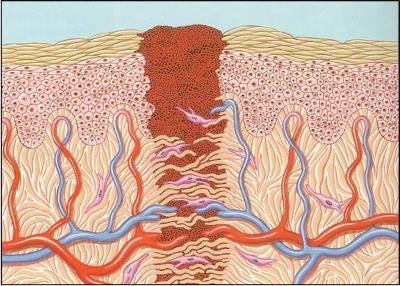

Bottom line: In general, it is not harmful to get a wound wet after 24 hours. We don’t know exactly why because of the paucity of the literature, but think about it. The water that we shower or bathe in is the same water that we drink. It’s very close to sterile. When we do shower or bathe, the bacteria that come in contact with the wound are our normal skin flora, which are already in and on the wound. Plus, most incisions that have been closed are water-tight within about 24 hours. It’s more likely that using soap and water is good for you because it washes away tons of bacteria, including the pathogens!

- Prospective randomised trial of the early postoperative bathing. BMJ 19 in June 1976: 1506-1507, 1976.

- Wound care after posterior spinal surgery. Does early grading affect the rate of wound complications? Spine (Phila PA 1976) 21(18):2160-2162, 1996.

- Does a shower with postoperative wound healing at risk? Chirurg 68(7): 715-717, 1997.

- Modification of postoperative wound healing by showering. Chirurg 71(2):234-236, 2000.

- Postoperative wound healing in wound-water contact. Zentralbl Chir 125(2):157-160, 2000.