CT scans are commonly used to aid the workup of patients with blunt trauma. They are occasionally useful in penetrating trauma, specifically when penetration into a body cavity is uncertain, and the patient has no hard signs that would send him or her immediately to the operating room.

Is there any role for CT in operative penetrating trauma, after the patient has already been to the OR? The dogma has always been that the eyeballs of the surgeon in the OR are better than any other imaging modality. Really? The surgical group at San Francisco General addressed this question by retrospectively reviewing 6 years of their operative penetrating injury registry data. They were interested in finding how many occult injuries (seen with CT but not by the surgeon) were found on a postop CT. A total of 225 patients who underwent operative management of penetrating abdomen or chest injury were included. Here are the factoids:

- Only 110 patients had a postop CT scan; 73 had scans within the first 24 hours, the other 37 were scanned later

- The rationale for early scan was to investigate retroperitoneal injury in half of patients, but frequently no indication was given (41%)

- The rationale for late scan was for workup of ileus in one-third or for evaluation of new or unexpected clinical problems

- Occult injuries were found in about half of early CT patients (52%) and 22% of late CT patients

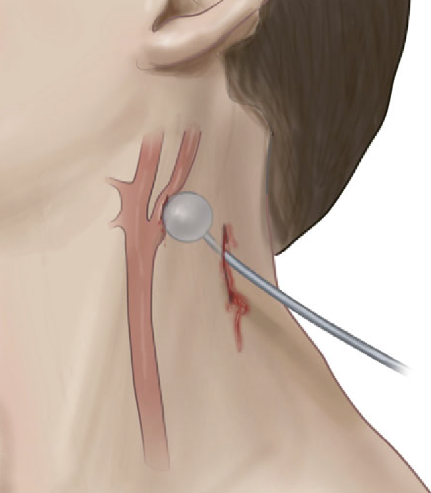

- The most common occult injuries were fractures, GU issues, regraded solid organ injury, and unrecognized vascular injuries

- Ten patients had management changes, including:

- Interventional radiology for four injuries with extravasation

- Operation for orthopedic or GU injury in seven patients

- One patient underwent surgery for an unstable spine fracture

Bottom line: There appears to be a significant benefit to sending some penetrating injury patients to CT in the early postop period. Specifically, those with injury to the retroperitoneum, deep into the liver, near the spine, or with multiple and complicated injuries would benefit. Simple stabs and gunshots that stay away from these areas/structures probably do not need follow-up imaging.

Reference: Routine computed tomography after recent operative exploration for penetrating trauma: What injuries do we miss? J Trauma 83(4):575-578, 2017.