In the last post, I described the first crucial step in the contemporary management of penetrating neck trauma, control of obvious external hemorrhage. Let’s move on to the nuts and bolts of figuring out what needs to be done about the injury.

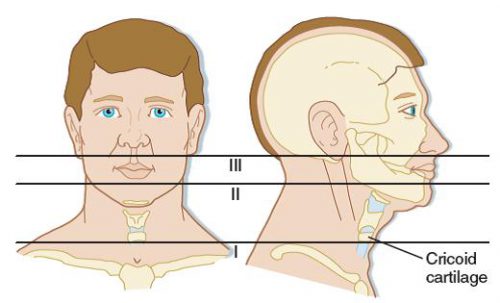

Now, it’s time to triage your patient based on clinical signs that predict the presence or absence of a significant injury. In the old days, the neck was conceptualized as three different zones that dictated the diagnostic and management algorithm.

We are now moving toward considering the neck as a single unit. The next decision point is to determine the risk for vascular or aerodigestive tract injury based on an examination for signs of injury. These signs have been divided into three groups.

Hard signs. These indicate a high risk for deeper injury and consist of the following:

- Vascular signs

- Refractory shock

- Pulsatile or difficult-to-control hemorrhage

- Large or expanding hematoma

- Audible bruit or palpable thrill (I hardly ever see anyone actually check the neck for these, so brush up your skills!)

- Aerodigestive signs

- Airway compromise or stridor

- Bubbles from the wound

- Significant subcutaneous emphysema

- Major hematemesis

- Massive hemoptysis

- Neurologic signs

- Neurologic deficits that suggest embolic strokes from a vascular injury

Soft signs. These suggest an intermediate risk for injury and are:

- Vascular signs

- Small or stable hematoma

- History of bleeding or hypotension that has resolved

- Active venous oozing

- Pulse volume or blood pressure discrepancy (this suggests a thoracic vascular injury)

- Aerodigestive signs

- Hoarseness or any voice changes

- Painful swallowing

- Difficult swallowing

- Mild subcutaneous emphysema

- Minor hematemesis

- Minor hemoptysis

- Neurologic signs

- Local neurologic deficit (direct injury to local nervous structures)

No signs. Obviously, this suggests a low risk of injury.

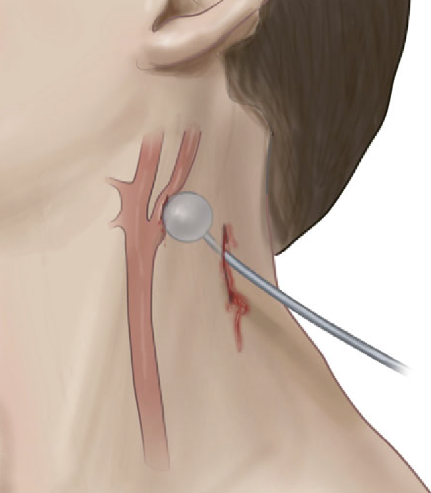

Once the level of risk has been determined, a course of action can be planned. Most patients with hard signs will require operative intervention. Plain x-rays with skin markers in place may help visualize retained foreign bodies and their relationship to bony structures. If the signs are immediately life-threatening, this step should be skipped, and operative exploration should be performed immediately. If the patient is stable and the injuries may be outside the easily accessible area of the neck (the old Zone II), a multi-detector CT angiogram (MDCTA) may help with operative planning. It may also identify patients eligible for endovascular repair.

Patients with soft signs have a lower risk of injury and should immediately undergo MDCTA. This scan has very high sensitivity and specificity in this group.

Finally, patients with no signs of deeper injury rarely need any intervention. Small series suggest that these patients could potentially be discharged from the ED. However, most trauma professionals will be uncomfortable with the thought of this. MDCTA is a low-risk test; until we know better, it’s probably best to obtain it before discharge.

Bottom line: I have described the initial assessment and management of patients with penetrating neck injury using the newer method using signs of injury in place of the old zones of injury. Nuances are still possible, such as what to do if the MDCTA is indeterminate for a vascular or aerodigestive injury. Fortunately, that is fodder for another post!

Reference: Approach to Penetrating Neck Trauma: What You Need to Know. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024 Mar 25. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004292. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38523116.