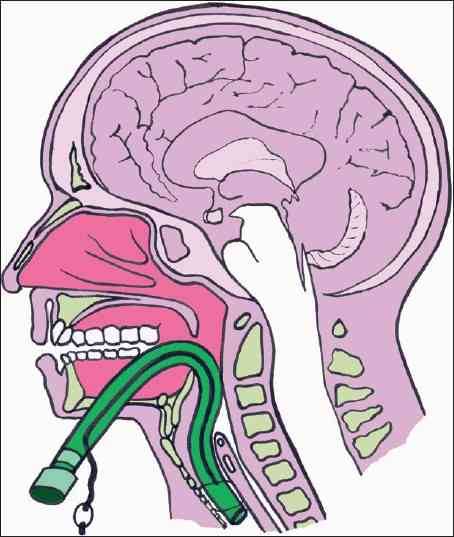

How often do trauma professionals hear that? Patients intubated in the ED (or before) almost universally have a chest x-ray taken to check endotracheal tube position. And due to variations in body habitus (and sometimes number of teeth), the tube may not end up just where we want it. So look at how deep or shallow it is and adjust it by the number of centimeters out of the correct position it should be, right?

Not so fast! A small, prospective study from Yale looked at endotracheal tube adjustment in ICU patients using tube markings and the patients incisors. Their “ideal” tube position has the tip between 2 and 4 cm from the carina. Any patients with an ET tube outside these parameters was included in the study. Here are the interesting tidbits:

- There were only 55 patients who met criteria for the study. No denominator information was give, so we can’t tell how good or bad the intubators were initially.

- Most tubes that needed adjustment were too far out. The median starting position was at 7cm above the carina (!),

- A smaller number were too deep (median position 0.7cm). These were mostly in women.

- The usual intended adjustment was 2cm. The actual distance moved after manipulation was half that (1.1cm).

Bottom line: Endotracheal tube repositioning based on tube markings at the incisors is not as accurate as you may think. Patient body habitus and reluctance to pull a tube out too far probably are factors here. So be prepared to readjust a second time unless you intentionally add an extra centimeter to your intended tube movement.

Related post:

Reference: Repositioning endotracheal tubes in the intensive care unit: Depth changes poorly correlate with postrepositioning radiographic location. J Trauma 75(1):146-149, 2013.