We are in the midst of Coronavirus mania! Every hospital in the country is scrambling to figure out what to do to meet the rapidly increasing demand for screening and access to care that has been so unexpectedly thrust upon us.

Trauma professionals will be profoundly affected as well. We are a scarce resource in the first place, and I’m speaking of those in all disciplines from prehospital through rehab. And since the SARS-CoV-2 virus seems to be so widespread and our testing abilities so limited, it is a challenge to protect ourselves from contracting it. Given how scarce we are, losing even a few to self-imposed quarantine (or worse) would be very disruptive to the health care of the trauma patients we normally take care of.

The key is to try to limit exposure to the Coronavirus as much as possible. Hospitals are now very diligent about screening patients and their families as they enter the hospital. However, the trauma activation patient is a potential wild card.

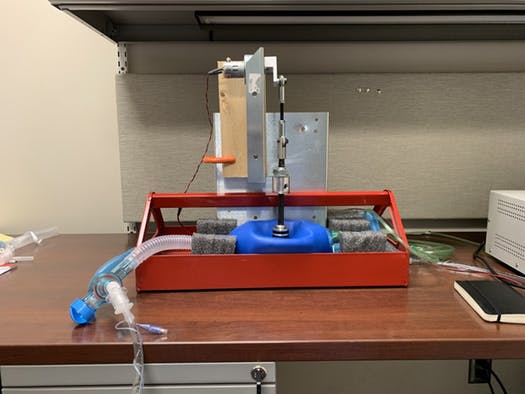

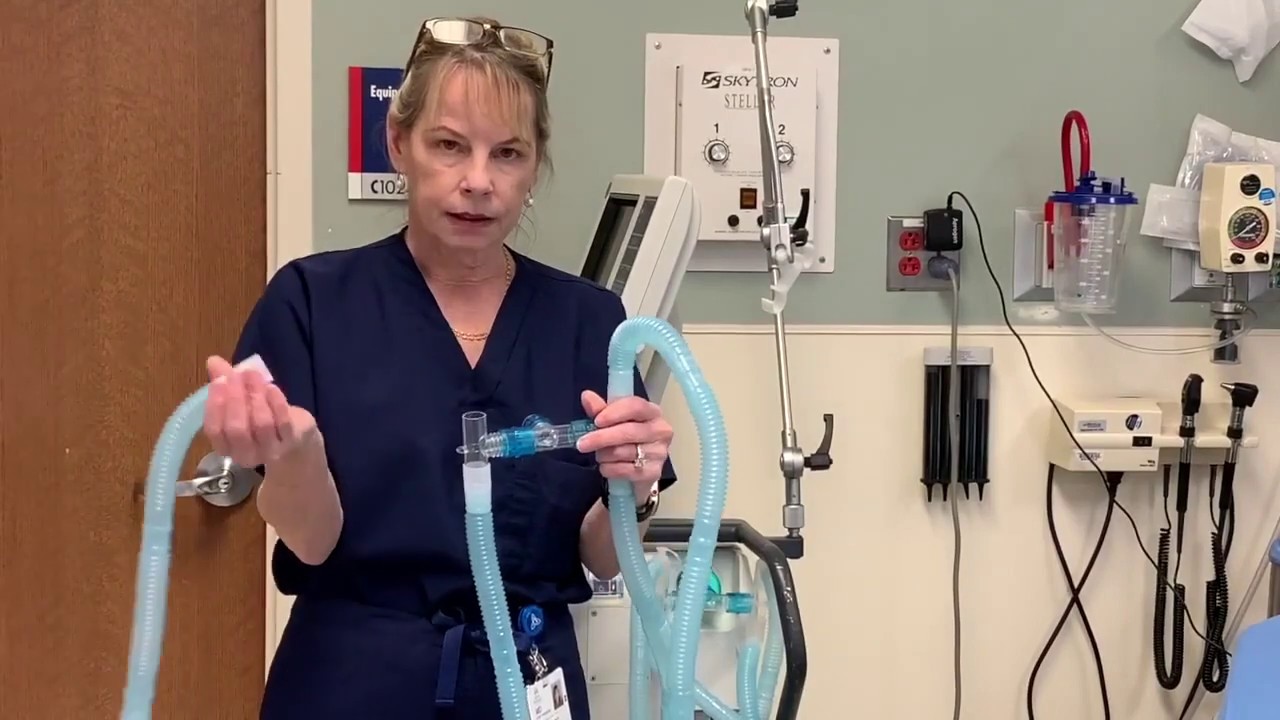

What can be done to protect the trauma professionals assembling to take care of a trauma activation patient, who should probably be considered infected until proven otherwise? The most obvious answer is to escalate the normal personal protective measures to include the same garb worn for treating patients with known or suspected infection. This includes N95 masks and full face shields.

Unfortunately, this is not practical due to the extreme shortages of this equipment. But what we can do is optimize our trauma team and provide a more informed and graduated response.

Here are my recommendations:

- Drastically reduce overtriage. Most busy trauma centers have overtriage rates (trauma activation for patients with low acuity and/or do not meet activation criteria) around 50%, and sometimes higher. Frequently, these are patients who did not really need to be met by the full trauma team. How can you do this?

- Eliminate superfluous activation criteria; keep only your physiologic and anatomic ones. These generally correlate with Steps 1 and 2 of the CDC triage criteria for transfer to a trauma center used by your EMS providers. Eliminate all mechanism of injury criteria except for penetrating injury. This includes falls, pedestrian struck, vehicle intrusions, etc. Then eliminate anything else that doesn’t fall into these categories. You are essentially converting to a bare bones single-tier activation system.

- Eliminate the ability of prehospital providers to call a field activation on anything other than your activation criteria (or Step 1 and Step 2 CDC criteria. This may be difficult or confusing if they service several centers that normally have different criteria. The person taking the radio/phone call and initiating the team page should not activate the team unless one of the physiologic or anatomic criteria are specifically mentioned. All other transports should be met by an emergency physician who will then use their clinical judgement to activate the full team.

- Eliminate superfluous trauma team members. This includes students, shadowing providers, observers, extra residents, and anyone else who does not have an essential role in the room.

- Call the entire team, but only use who you need. Determine the makeup of your core team. One physician, two nurses, a tech, and a scribe? This will vary by center. They should dawn protective gear that is as effective (and available) as possible. (This may not be face shields and N95 masks if you are a busy center and don’t have many in stock.) The others should remain available outside the room and be called in only if necessary (pharmacist, respiratory therapy, additional physicians or APPs, etc). All other normal team personnel can then be dismissed and disperse.

- Release active team members who are no longer needed. As the resuscitation winds down and team members complete their tasks, send them away.

- Reduce the post-resuscitation transport team to the minimum necessary. This will depend on the patient’s condition. Are they stable, awake, and alert? Or intubated and traveling with a rapid infuser? Assign personnel appropriately.

Bottom line: Things have changed for a while and the old rules may not completely apply. Critically look at everything you do to see if it is still reasonable and necessary. Always keep the safety of your patient at heart. But don’t lose sight of the fact that you won’t be able to help anyone in the future if you are quarantined at home.

This crisis will only last for a few months, but it should cause us to question business as usual. We may discover that some of what we do is not a necessary as we thought!

I’m very interested in what others are doing with their resuscitation teams and trauma services to increase safety. Please share on Twitter, or feel free to email me.