I just finished a summary of the Australian consensus paper regarding anticoagulants (and anti-platelet agents) in patients with hemorrhagic TBI. One of the issues addressed was reversal of these agents. Today I’m going to provide more specific information on one of the new reversal agents, Andexxa (recombinant Factor Xa, inactivated-zhzo).

First, maybe someone can help me here. What does zhzo mean? I’ve done a deep dive including a review of the FDA filings, and still can’t figure out what this is. I have a hard enough time with the thousands of something-umab monoclonal antibody products out there. Now we’re adding on a bunch of z’s to the end of drug names?

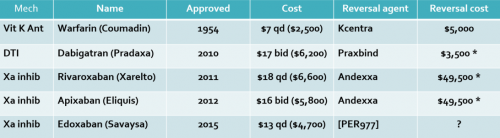

There are currently two classes of direct oral anticoagulant drugs (DOACs) available, direct thrombin inhibitors and Factor Xa inhibitors. Andexxa was designed to reverse the latter by providing a lookalike of Factor Xa to selectively bind to apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto).

The Austrian consensus paper I previously discussed recommended giving Andexxa in patients taking apixaban or rivaroxaban if it was not possible to show that the drugs were non-therapeutic. This means that if your lab could not measure anti-Factor Xa levels in a timely manner and the patient was known to be taking one of these agents, reversal should be considered.

Sounds cut and dried, right? Your patient is taking a Factor Xa inhibitor and they are bleeding, so give the reversal agent. Unfortunately, it’s much more complicated than that.

- The half-life of Andexxa is much shorter than that of the drugs it reverses. The reversal effect of Andexxa begins to wear off two hours after administration, and is gone by four hours. On the other hand, the half life of rivaroxaban is 10+ hours in the elderly. The half-life of apixaban is even longer, 12 hours. This means that it is likely that multiple doses of Andexxa would be necessary to maintain reversal.

- There are no studies comparing use of Andexxa with the current standard of care (prothrombin complex concentrate, PCC). The ANNEXA-4 study tried to do this. It was a single-arm observational study with 352 subjects. These patients were given Andexxa if major bleeding occurred within 18 hours of their DOAC dose. Two thirds of the patients had intracranial bleeding. All were given a bolus followed by a two hour drip. All showed dramatic drops in anti-Factor Xa levels, and 82% of patients had good or excellent control of hemorrhage. However, 15% died and 10% developed thrombotic complications.

- The FDA clinical reviewers recommended against approval due to the lack of evidence for clinical efficacy. The director for the Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies overruled the reviewers and allowed approval until such time a definitive study was completed. So far there have been no justifiable claims that Andexxa is superior to PCC.

- To be fair, PCC has not been compared to placebo either. So we don’t really know how useful it is when treating bleeding after DOAC administration.

- Andexxa is very expensive. Old literature showed a single dose price of $49,500 but this has been revised downward. Effective in October 2019, Medicare agreed to reimburse a hospital about $18,000 for Andexxa over and above the DRG for the patient’s care. Remember, due to the half life of the Factor Xa inhibitors, two doses may be needed. This comes to about $36,000, which is much higher than the cost for PCC (about $4,000).

Bottom line: Any hospital considering adding Andexxa to their formulary should pay attention to all of the factors listed above and do the math for themselves. Given the growing number of patients being placed on DOACs, the financial and clinical impact will continue to grow. Is the cost and risk of this therapy justified by the meager clinical efficacy data available?

References:

- Full Study Report of Andexanet Alfa for Bleeding Associated with Factor Xa Inhibitors. NEJM 380(14):1326-1335, 2019.

- Key Points to Consider When Evaluating Andexxa for Formulary Addition. Neurocrit Care epub ahead of print, 22 Oct 2019.