In this series, I will review the two major techniques for addressing troublesome bleeding from pelvic fractures. This post will review the evolution of packing techniques and more fully describe the concept of preperitoneal packing. Next, I’ll review an early paper that compared the snippets of information we had to angioembolization. In the last post in the series, I’ll discuss a paper in press that compares the efficacy and hospital charges of the two techniques.

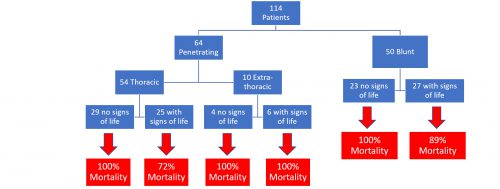

A multi-center trial published in 2015 showed an astounding 32% mortality rate for patients with shock from pelvic fracture. As I continue to preach, going anywhere but the OR is dangerous for the patient. Unfortunately, it’s generally not feasible to operatively fix the pelvis acutely, and external fixation has limited impact on ongoing hemorrhage.

If the patient can be stabilized to some degree, interventional radiology can be very helpful. Unfortunately, access after hours involves some degree of time delay. Ideally, the team arrives in 30 minutes or less. But the patient may not be ready, so time to procedure may increase significantly.

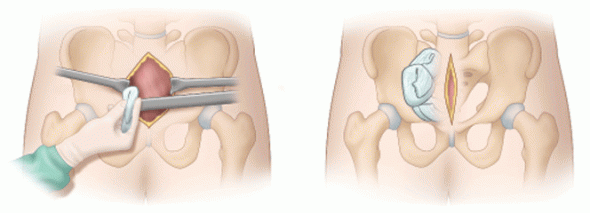

Preperitoneal packing of the pelvis (PPP) has now become popular. Years ago, we tried to pack the pelvis from the inside (peritoneal cavity), but it never worked very well. You can push sponges deep into the pelvis as firmly as you want, but the intestines will not keep them from expanding back out of the pelvis.

PPP entails making a lower midline incision but not entering the peritoneal cavity. A hand is then slid along the anterior surface of the peritoneum around the inside of the iliac wing. Sponges can then be pushed around toward the sacrum, applying direct pressure over bleeding fracture sites and the overlying tissues.

Image courtesy of ACSSurgery.com

But does it work? Denver Health performed an 11 year retrospective review of their experience with 2293 patients with pelvic fractures. They looked at time to intervention, blood product usage, and mortality.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 128 patients underwent PPP

- Most were younger (mean age 43) and badly injured (mean ISS 48)

- Median time from door to OR was 44 minutes

- Patients received an average of 8 units of RBCs intraoperatively, and an additional 3 units in the ensuing 24 hours

- Overall mortality was 21% (27 of 128), but 9 (7%) were due to severe head injury

Bottom line: Compared to other published studies, time to “definitive management” with PPP was very short. Blood usage also dropped quickly after the procedure. Mortality seems to be much better than expected at about 13%. These results suggest that if you have to wait for angiography, or your patient is too unstable to go there, run to the OR first to do some PPP.

And don’t forget these other important management tips:

- If you see any posterior pelvic fracture on the initial pelvic x-ray, call for blood

- If the blood pressure softens at any point activate your massive transfusion protocol

- Apply a binder, especially for open book type fractures

- Always get a CT in stable patients to help your orthopedic surgeons plan, and to identify contrast blushes

- If the patient has to go to OR first to stabilize them, consider angiography afterwards. You’ll probably find something they can fix.

- Think about using your hybrid OR!

Reference: Preperitoneal pelvic packing reduces mortality in patients with life-threatening hemorrhage due to unstable pelvic fractures. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 82(2), 233–242.