We are moving into a world where more and more people are taking anticoagulants. And as the number of possible anticoagulant drugs increases, the prospect of reversing them becomes more complicated. Just as the price of those medications continues to climb, so does the price of the agents used to reverse them.

The decision to reverse an anticoagulant, the speed of reversal, and choice of reversal agent all depend on an assessment of the severity of bleeding. Some reversal drugs such as prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) act almost immediately but are expensive. Others take time, but are cheaper such as plasma and vitamin K.

Unfortunately, trying to come to a consensus on what constitutes life-threatening bleeding is very difficult. Over the years, numerous studies have been done, with almost as many definitions of bleeding. As you know, I am generally against reinventing the wheel. Borrowing someone else’s excellent work saves a lot of time and anguish.

But when it comes to defining dangerous bleeding, we are faced with so many definitions, it just begs for a “unifying theory.” I’ll show you some of the more commonly used definitions below. At the very bottom, I’ve included a link to a very comprehensive list of definitions that have been used.

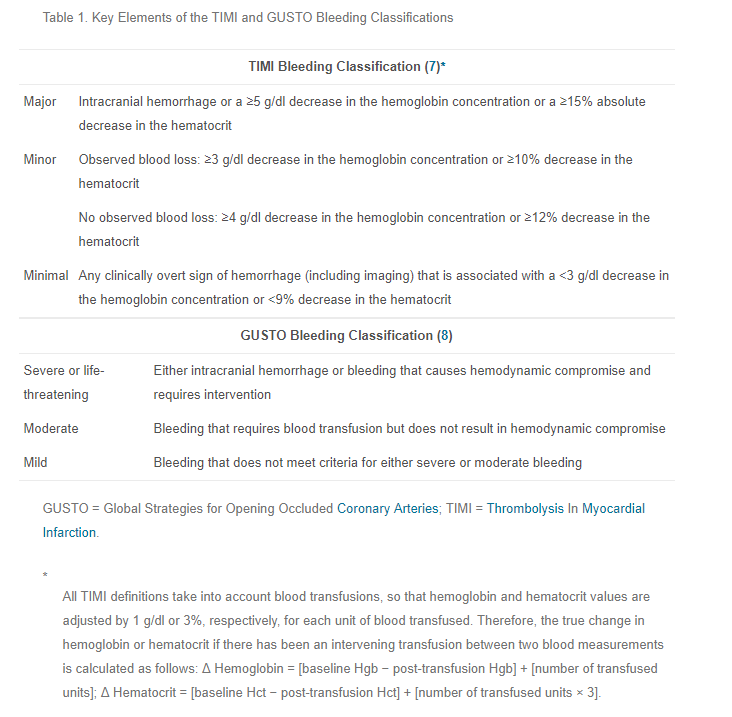

First, there’s TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction trial) and GUSTO (Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries trial). (Please remember how much I dislike cute acronyms.)

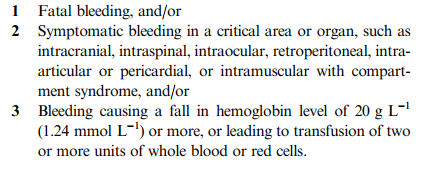

The following consolidated definition was published in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostsis way back in 2005:

If you want to look at a more comprehensive list of a lot of definitions, download the document from the link below.

So how do we make sense of all this? As trauma professionals and clinicians on the front line of anticoagulant reversal, we need a simple definition. I’ve recently looked over as many definitions as I could lay my hands on.

In my next post, I’ll propose a simplified set of definitions. And I’ll be very interested in your input and comments. They will ultimately end up as a definition that we will use at my own trauma center. And maybe yours.

Related post:

- Download the list of life-threatening bleeding definitions

- Pet peeve: not so cute medical study acronyms

Reference:

- Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 3: 692–694, 2005.