This is a perfect example of why you cannot just simply read an abstract. And in this case, you can’t just read the paper, either. You’ve got to critically think about it and see if the conclusions are reasonable. And if they are not, then you need to go back and try to figure out why it isn’t.

A study was recently published regarding bleeding after nonoperative management of splenic injury. The authors have been performing an early followup CT within 48 hours of admission for more than 12 years(!). They wrote this paper comparing their recent experience with a time interval before they implemented the practice.

Here are the factoids. Pay attention closely:

- 773 adult patients were retrospectively studied from 1995 to 2012

- Of 157 studied from 1995 to 1999, 83 (53%) were stable and treated nonoperatively. Ten failed, and all the rest underwent repeat CT after 7 days.

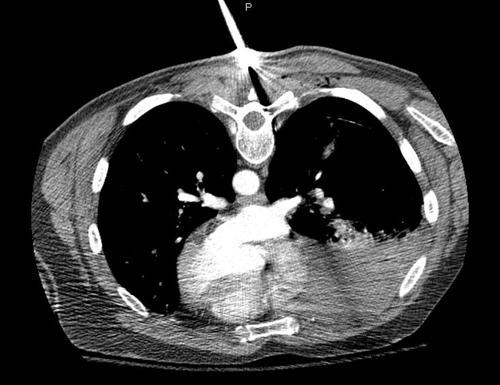

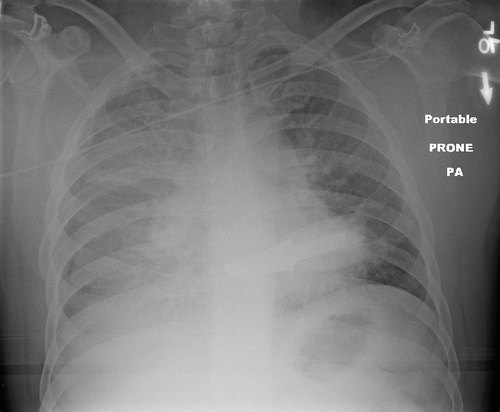

- After a “sentinel delayed splenic rupture event”, the protocol was revised, and a repeat CT was performed in all patients at 48 hours. Pseudoaneurysm or extravasation initially or after repeat scan prompted a trip to interventional radiology.

- Of 616 studied from 2000-2012, after the protocol change, 475 (77%) were stable and treated nonoperatively. Three failed, and it is unclear whether this happened before or after the repeat CT at 48 hours.

- 22 high risk lesions were found after the first scan, and 29 were found after the repeat. 20% of these were seen in Grade 1 and 2 injuries. All were sent for angiography.

- There were 4 complications of angiography (8%), with one requiring splenectomy.

- Length of stay decreased from 8 days to 6.

So it sounds like we should be doing repeat CT in all of our nonoperatively managed spleens, right? The failure rate decreased from 12% to less than 1%. Time in the hospital decreased significantly as well.

Wrong! Here are the problems/questions:

- Why were so many of their patients considered “unstable” and taken straight to OR (47% and 23%)?

- CT sensitivity for detecting high risk lesions in the 1990s was nothing like it is today.

- The accepted success rate for nonop management is about 95%, give or take. The 99.4% in this study suggests that some patients ended up going to OR who didn’t really need to, making this number look artificially high.

- The authors did not separate pseudoaneurysm from extravasation on CT. And they found them in Grade 1 and 2 injuries, which essentially never fail

- 472 people got an extra CT scan

- 4 people (8%) had complications from angiography, which is higher than the oft-cited 2-3%. And one lost his spleen because of it.

- Is a 6 day hospital stay reasonable or necessary?

Bottom line: This paper illustrates two things:

- If you look at your data without the context of what others have done, you can’t tell if it’s an outlier or not; and

- It’s interesting what reflexively reacting to a single adverse event can make us do.

The entire protocol is based on one bad experience at this hospital in 1999. Since then, a substantial number of people have been subjected to additional radiation and the possibility of harm in the interventional suite. How can so many other trauma centers use only a single CT scan and have excellent results?

At Regions Hospital, we see in excess of 100 spleen injuries per year. A small percentage are truly unstable and go immediately to OR. About 97% of the remaining stable patients are successfully managed nonoperatively, and only one or two return annually with delayed bleeding. It is seldom immediately life-threatening, especially if the patient has been informed about clinical signs and symptoms they should be looking for. And our average length of stay is 2-3 days depending on grade.

Never read just the abstract. Take the rest of the manuscript with a grain of salt. And think!

Reference: Delayed hemorrhagic complications in the nonoperative management of blunt splenic trauma: early screening leads to a decrease in failure rate. J Trauma 76(6):1349-1353, 2014.