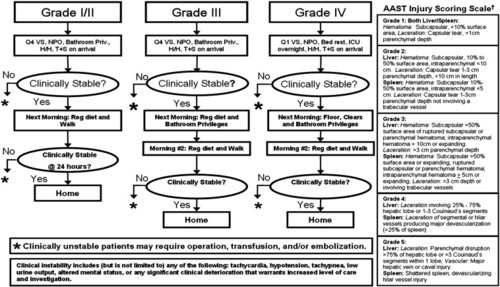

There was an interesting article released in the Journal of Pediatric Surgery in May about spleen and liver injury management in children. It’s interesting because if you just look at the title, you might just skip over it. The title suggests that it describes reducing scheduled phlebotomy in kids who are undergoing solid organ injury management. But the real meat of this article has to do with the protocol they are using to treat the children.

Nonoperative management of these injuries in children started becoming popular 40 years ago (!). But for decades, everyone put their own spin on how to do it. Bed rest for a week (or more). NPO for days! Limited physical activity for extended periods. Then the American Pediatric Surgery Association (APSA) published a set of guidelines about 15 years ago that took some of the guesswork out of it.

Although nonoperative management of these injuries in kids preceded its adoption in adults by a nearly two decades, it has languished in the APSA format for quite some time. Many pediatric surgeons still use these guidelines, even though adult spleen and liver injury management have advanced to shorter and more streamlined care.

We adopted a solid organ management guideline at Regions Hospital over ten years ago, and have made a few minor tweaks over the years. Nowadays, our grade I-III injuries can be home as early as 36 hours after admission, and frequently are. Grades IV and V are eligible to be discharged after just 24 more hours if they have no other injuries to keep them in the hospital.There are very rare failures.

I’ll detail the factoids about the phlebotomy part of this paper in tomorrow’s post. But I do want to show you the more aggressive protocol the authors are using (one of whom authored the original APSA guideline).

Here it is:

Bottom line: Note how quickly children are allowed to get up, eat, and get out of the hospital using the “new” protocol. Many adult centers have been using similar ones for years. It’s nice to see that adult and pediatric protocols are finally beginning to converge. After all, we figured out our current adult management based on our experience with kids 30 years ago!

Related posts:

- Printable version of the protocol above

- Regions Hospital solid organ management protocol – adult

- Regions Hospital solid organ management protocol – peds

- Phlebotomy and pediatric solid organ injury – Part 2

Reference: Reducing scheduled phlebotomy in stable pediatric patients with liver or spleen injury. J Ped Surg 49(5):759-762, 2014.