This paper was presented at EAST in 2013, and this is an update of that work using the entire manuscript which has now been published.

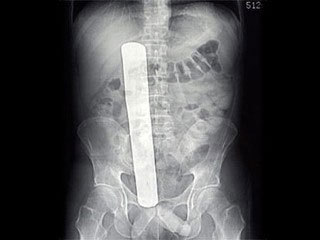

The standard of care in most high level trauma centers is to involve neurosurgeons in the care of patients with significant traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, not all hospitals that take care of trauma patients have immediate availability of this resource. The University of Arizona at Tucson looked at management of these patients by their acute care surgeons.

The authors did a retrospective cohort study of patients at their center who had a mild TBI and positive head CT, managed with or without neurosurgery consultation, over a two year period. They matched the patients with and without neurosurgical consultation for age, GCS, AIS-Head and presence of skull fracture and intracranial hemorrhage.

A total of 90 patients with and 180 patients without neurosurgical involvement were reviewed. Here are the factoids:

- Hospital admission rate was identical for both groups (87-89%)

- ICU admission was significantly higher if neurosurgeons were involved (20% vs 44%)

- Repeat head CT was ordered more than 3 times as often by neurosurgeons (20% vs 86%)

- Post-discharge head CT was ordered more often by neurosurgeons, but was not significantly different (5% vs 12%)

- There were no surgical interventions, in-hospital mortality, or readmissions within 30 days in either group.

- Cost of the hospital stay was significantly increased if neurosurgery was consulted.

Bottom line: Can surgeons safely manage select patients with intracranial injury? Granted, this is a small, retrospective study, but the answer is probably yes. The majority of patients with mild to moderate TBI with small intracranial bleeds or skull fractures do well despite everything we throw at them. And it appears that surgeons use fewer resources managing them than neurosurgeons do. The keys to being able to use this type of system are to identify at-risk patients who really do need a neurosurgeon early, and having a quick way to get the neurosurgeon involved (by consultation or hospital transfer). Having a specific practice guideline for management is essential as well. As neurosurgery involvement in acute trauma declines, this concept will become more and more pertinent.

Related posts:

Reference: The acute care surgery model: managing traumatic brain injury without an inpatient neurosurgical consultation. J Trauma 75(1):102-105, 2013.