This is the final installment of my series on the tertiary survey for trauma. For years, this exam was performed by trauma surgeons or residents. However, over the years advanced practice providers (APPs) such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners have become more common in trauma. It is now commonplace for these providers to participate on the trauma service, perform procedures, and document examinations such as the tertiary survey.

But until now, no one has compared the accuracy of this exam when performed by a physician vs an APP. One would assume that the results should be the same, but as we’ve seen time and time again, common sense doesn’t always pan out. A group at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Queensland, Australia tried to answer this question using a retrospective review of their experience.

This busy trauma center admits about 2,250 patients per year, and began to employ clinical nurse consultants on the trauma service nearly ten years ago. Since there was no formal trauma curriculum for these nurses, they were required to complete the Trauma Nursing Core Curriculum (TNCC) or an equivalent prior to hire. The nurses were supervised by one of the trauma / emergency physicians.

For this study, 165 patients who underwent a tertiary survey by both an emergency medicine resident and a trauma nurse over a three year period were reviewed. The surveys were typically performed within 24 hours of admission to a ward bed or 24 hours before transfer from ICU to the ward. Typically, the resident and nurse tertiary surveys were performed within 30 minutes of each other to avoid any effects from injury progression.

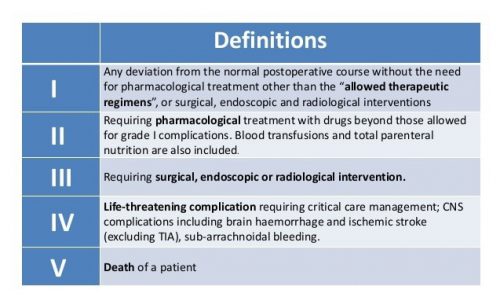

All missed injuries were graded for severity by an attending physician using the Clavien-Dindo system. Here’s what it looks like:

And here are the factoids:

- A total of 3,065 patients had a tertiary survey performed during the study period, but only 165 had it performed by both a resident and an APP

- Based on their surveys, additional investigations were ordered in 35 patients, 14 by the trauma nurse, 11 by the resident, and 10 by both

- Eight of 14 studies ordered by the nurse identified a missed injury, two of 11 studies ordered by the resident did, and two were identified in the studies ordered by both

- Of the 12 identified missed injuries, the Clavien-Dindo (C-D) score was 0 in one, I in ten patients, and III (required surgery) in one

- The nurses identified a higher number of missed injuries (10 of 24) than the residents (4 of 21) without significantly increasing the number of tests ordered

The authors concluded that performance of the nurses was similar to that of the house officers.

Bottom line: Maybe the authors were trying to be gentle on their residents. But it looks to me like the trauma nurses did a much better job of finding occult injuries. I wish the authors had broken down the C-D scores to see which group identified the score III patient.

To be fair, this study has some significant limitations. Out of more than 3,000 eligible patients, only 165 had a dual tertiary survey. So the sample may not be representative. But the results were impressive enough that I would speculate the results of a larger group may be similar.

So I think it is safe to assume that APPs (specifically nurse practitioners, but this can probably be generalized to physician assistants as well) can do a tertiary survey just as well as a resident. And possibly better!

Reference: Trauma tertiary survey: trauma service medical officers and trauma nurses detect similar rates of missed injuries. J Trauma Nursing 28(3):166-172, 2021.