Although you may not agree with this at first, communicating with our patients is one of the most important things we do as trauma professionals. You can be the “best” doctor, nurse or paramedic in the world, but if you can’t communicate well your patients will have nothing good to say about your care of them.

The most important skill needed for good communication is empathy. You need to be able to put yourself in their position. Imagine what you would want if you were on the receiving end of the information you are about to deliver. What would you say if you were talking to your spouse, your mother, or your child?

Next, think about what kinds of things they would want to know. In trauma, they obviously want to know information about the injuries. Patients and families also need to hear about the short term and long term plans. What’s going to happen in the next few hours? Will surgery be needed? When? How long will I be in the hospital? How long will I be out of work?

Many of these questions are difficult to answer at the time of admission after trauma. If you don’t know or it’s impossible to determine, say so. Experienced clinicians can make some pretty good guesses, but should always qualify their answers. You should make it clear that you are giving an estimate, and that things may very well change. Also explain that as these changes occur and time passes, you will give better estimates. And no BS! They can smell that right away.

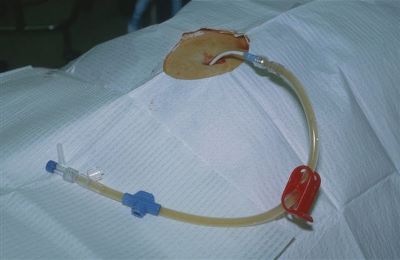

One of the most important things to remember is the “keep it simple” mandate. Our patients and their families are smart. Although they may not know the lingo that we are familiar with, they can grasp the concepts of what is happening. Be careful to keep your explanations understandable, and don’t make the mistake of using any complicated medical terms. Imagine the surprise of the patient when they find out what “we’re going to insert a Foley catheter now, sir” really means. Also keep in mind that the patients and their families are stressed, and may not be able to concentrate on or remember everything you say. Repetition is good in these situations.

Bottom line: Communication after major trauma is challenging. Remember, if the families don’t get what you’re saying, it’s your fault, not theirs.