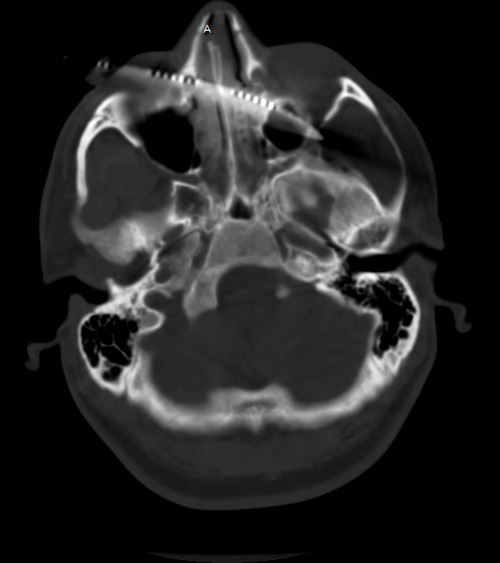

Our patient with the steak knife to the head has been evaluated by CT. The scan shows that the blade enters the right orbit, passing through the medial orbital wall into the ethmoid sinus, turbinates and nasal septum. It then passes into the left orbit along the posterior floor and exits the apex. The optic nerves are not involved, but there may be involvement of the rectus or oblique muscles to the globe. There does not appear to be any involvement of the maxillary sinus.

See why a good exam is important? Gross visual acuity and extra-ocular muscle testing is very important here. Miraculously, all are intact. So now what?

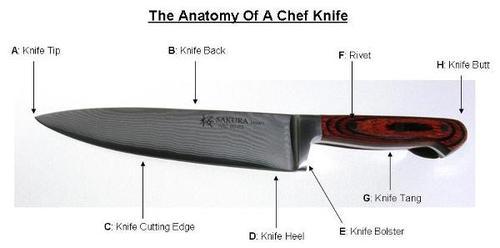

Just yank it out? Absolutely not! Although there is no gross bleeding from the nose or mouth, and none is seen on CT, that doesn’t mean there won’t be! The patient needs to go to the OR, and it may be helpful to have a facial surgeon present just in case. Scopes for evaluating the sinuses and packing materials should be readily available.

Under sedation, the knife can be smoothly withdrawn. An awake patient can tell you how it feels, and whether he is experiencing any bleeding or ocualr changes. If in doubt, the sinuses can be scoped and the globes re-examined.

Note: If troublesome bleeding does occur, this is not an area that is amenable to surgical exploration. The only realistic options available are packing and angioembolization.