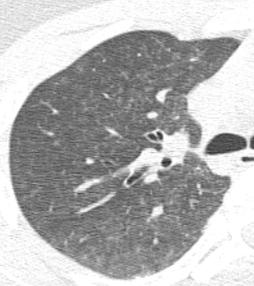

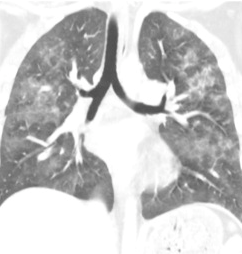

Hemothorax is a common complication of chest trauma, occurring in about one third of cases. It is commonly treated with a chest tube, which usually takes care of the problem. But in a few cases some blood remains, which can result in an entrapped lung or empyema.

There are several management options. Historically, these patients underwent thoracotomy to peel out the fibrinous collection stuck to lung and chest wall. This has given way to the more humane VATS procedure (video assisted thoracoscopic surgery) which accomplishes the same thing using a scope. In some cases, another tube can be inserted, sometimes under CT guidance, to try to drain the blood.

So what about lytics? It’s fibrin, right? So why not just dissolve it with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)? There have been very few studies published over the years. The most recent was in 2014. I’ll review it today, and another tomorrow. Finally, I’ll give you my thoughts on the best way to deal with retained hemothorax.

Here are the factoids:

- This was a single center, retrospective review of data from 1.5 years beginning in 2009

- A total of seven patients were identified, and most had hemothorax due to rib fractures. Three presented immediately after their injury, 4 were delayed.

- Median time from injury to chest tube placement was 11 days

- Median time the chest tube was in place was 13 days, with an average hospital stay of 14 days

- Patients received 1 to 5 treatments, averaging 24mg per dose

- There was one death in the group, unrelated to TPA treatment

- No patient “required” VATS, but one underwent thoracotomy, which turned out to be for a malignancy

Bottom line: The authors conclude that tPA use for busting retained hemothorax is both safe and effective. Really? With only seven patients? The biggest problem with this study is that it uses old, retrospective data. We have no idea why these patients were selected for tPA in this 5-year old cohort of patients. Why did it take so long to put in chest tubes? Why did the chest tubes stay in so long? Maybe this is why they were in the hospital so long?

Plus, tPA is expensive. A 100mg vial runs about $6000. Does repeatedly using an expensive drug and keeping a patient in the hospital an extra week or so make financial sense? So it better work damn well, and this small series doesn’t demonstrate that.

Tomorrow, I’ll look at the next most recent paper on the topic, from way back in 2004.

Reference: Evaluation of chest tube administration of tissue plasminogen activator to treat retained hemothorax. Am J Surg 267(6):960-963, 2014.