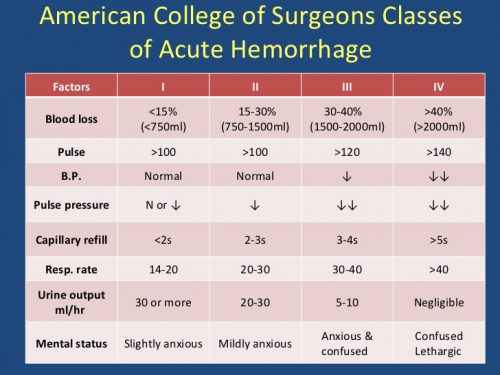

Trauma patients don’t always behave the way we would like. They continually surprise us, sometimes for the better, when they recover more quickly and completely than we thought. But sometimes, it’s for the worse. They occasionally crash when we think everything is going so well.

The crashing patient is obviously in need of help, and most trauma professionals know what to do. But then there’s the hypotensive patient. The BP just dropped to 84, and it’s not budging. Many don’t see this for what it is: a slow-motion crash. And they want to do things they wouldn’t think of doing to a crashing patient. Like go to CT, do some more stuff in the ED because that BP cuff just has to be wrong, or call interventional radiology and wait for 45 minutes.

But here’s the third law of trauma:

The only place an unstable trauma patient can go is to the OR.

Bottom line: By definition, an unstable trauma patient is bleeding to death until proven otherwise (the second law, remember?). Radiation can’t fix that. Neither can playing around in the resuscitation room unless the bleeding is spraying you in the face. The surgeon must quickly figure out which body cavity is the culprit and address it immediately. And the only place with the proper tools to do that is an operating room.