This case involves an accidental nail gun injury to the neck. The patient is hemodynamically stable, neurologically intact, the airway is patent and not threatened, and there is no apparent hematoma. There is a small puncture near the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the right, fairly high on the neck. The nail is not palpable on either side. And the patient only complains of a little discomfort when he swallows.

What to do? First, the patient has passed all the initial decision points that would send us straight to the OR (ABC problems in ATLS jargon). But, per physical exam and initial imaging, the nail must obviously come out. We just have to figure out what we need to know before we take it out, and determine the best way to retrieve it.

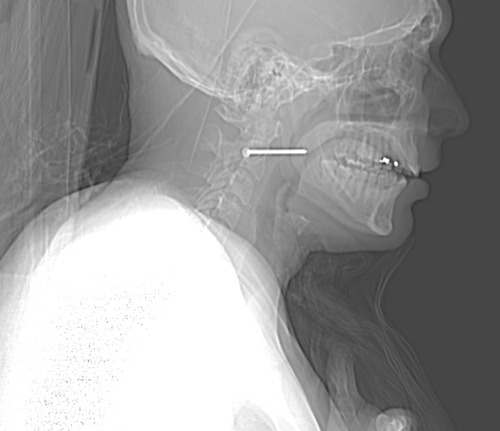

Given the patient’s stability, additional imaging will be helpful. Views in different planes, and details of what the nail might have passed through will be invaluable. The recommended study is a CT angio of the neck. This will give good information about nearby structures and the vasculature. And software reconstructions will provide good 2D/3D information for removal planning. Here’s a lateral view.

The nail is located in front of the body of C2. It appears to be high enough to be near the pharynx, but well above trachea and esophagus. You can also see that the nail entered a little posteriorly, and travels right to left and forward.

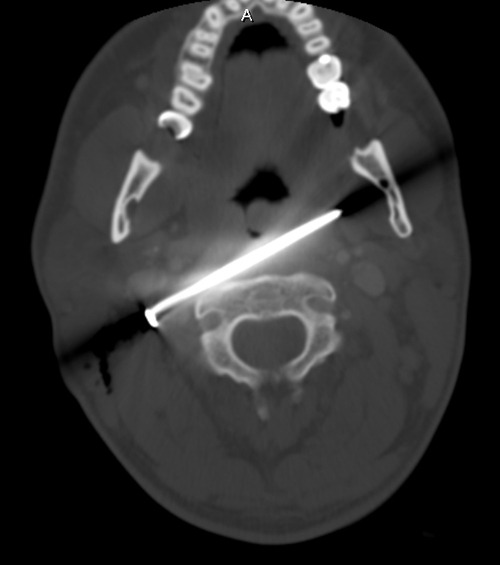

Here’s a representative CT slice.

The nail enters behind the carotids (just above the bifurcation) and IJ on the right, and ends anterior to them on the left. It passes very close to the posterior pharynx. So neurovascular structures are intact, and the aerodigestive tract is a maybe (back of the pharynx).

Obviously, this thing has to come out. The question is, how to do it? For you surgeons out there, tell me your choice of approach, incision, and instrumentation. Tweet/X or leave comments! Answers in the next post.