Yesterday I presented the case of a young man who shows up at the triage desk in your ED with “something wrong with his head.” I showed an AP skull film, which shows some kind of metallic foreign object. What is it? Where is it? What to do?

First, look at the image carefully. The object is metallic density and appears very thin. But remember, any diagnostic image you view is a 2D representation of a 3D space. You have no idea of the orientation of the object, or exactly where (front to back) it is located. He could be lying on top of it, or it could be stuck in his brain.

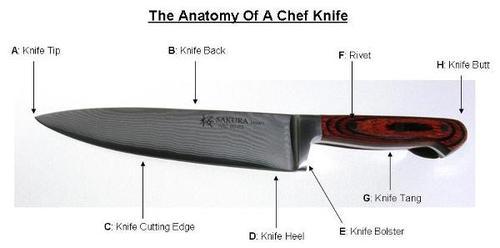

At the far left side of the image, the thin metal appears to get even thinner. Dead giveaway! Look at the diagram below.

The knife tang is the thin part of a knife that the handle is fastened to. @andrewjtagg tweeted that he wouldn’t mind seeing a lateral, so here it is.

Yes, it’s a knife. A steak knife to be exact. Somewhere in the middle of the face.

First off, you didn’t need to see these to start doing the right things. Since this is a penetrating injury to the “head, neck or torso” it should trigger any trauma center’s highest level of activation. He is whisked off to the trauma bay and quickly evaluated. He’s obviously awake and alert (he walked in), so what do you need to treat him, and how would you manage it?

Tweet or leave comments. More discussion (and pictures) on Monday.