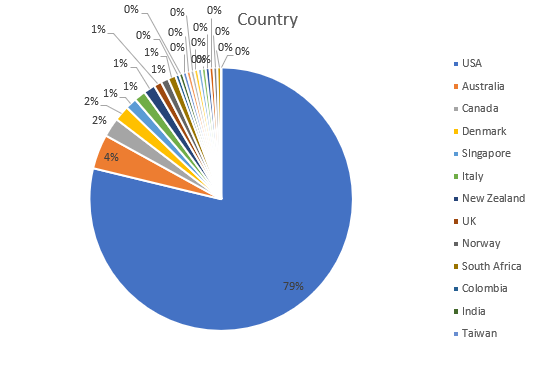

Again, thanks for all who submitted their survey answers. Here’s a rundown of the answers provided by US respondents. A few duplicates from the same hospitals have been merged into single answers for them. Total number of US centers for the tables below is 149.

Level of trauma center

| Level I | 83 |

| Level II | 37 |

| Level III | 15 |

| Level IV | 1 |

| Level V | 2 |

| Seeking verification/designation | 1 |

| No level | 10 |

How many ED thoracotomies are performed per year at your hospital?

| A few per year (<6) | 83 |

| About every month (6-15) | 35 |

| A couple of times a month (16-30) | 23 |

| About every week (31-52) | 8 |

What type of trauma do you perform ED thoracotomy for?

| Both blunt and penetrating | 79 |

| Penetrating | 64 |

| Blunt | 5 |

Do you use a practice guideline for ED thoracotomy?

| Yes | 86 |

| No | 47 |

| I’m not sure | 15 |

Do you use REBOA in your ED?

| No | 88 |

| Yes | 58 |

| I’m not sure | 3 |

And now for the questions you’ve been waiting for!

Who could perform ED thoracotomy at your hospital? (n=149)

| Surgeon | 145 | |

| Emergency physician | 109 | |

| Surgical resident / fellow | 93 | |

| Emergency medicine resident | 66 | |

| APP (PA, NP) | 2 | at one Level I and one Level V |

| Family physician | 1 | at one Level V |

| Family medicine resident | 1 | at one Level V |

Who usually performs ED thoracotomy at your hospital? (n=149)

| Surgeon | 115 | |

| Emergency physician | 25 | |

| Surgical resident / fellow | 69 | |

| Emergency medicine resident | 17 | |

| Never done one | 3 | |

| Family physician or family nurse practitioner | 1 | at one Level V |

Who usually performs ED thoracotomy at your hospital? (By trauma center level)

| Level | I (n=83) | II (n=37) | III (n=15) |

| Surgeon | 64 | 35 | 11 |

| Emergency physician | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Surgical resident | 63 | 4 | 1 |

| Emergency medicine resident | 12 | 1 | 2 |

| No one | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Join me tomorrow when I review the international data!