Last month, I posted a survey to find out the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) values trauma centers were using to trigger their highest level trauma activation. Nearly 150 people responded, providing a nice snapshot of practices worldwide. Today, I’ll summarize the responses and provide a bit of commentary about them.

There were a total of 147 respondents from around the world. I tried to eliminate duplicates from the same center using a self-reported postal code. However, this was an optional field, so there is the possibility that a few crept in. Readers from at least six countries outside the US also responded.

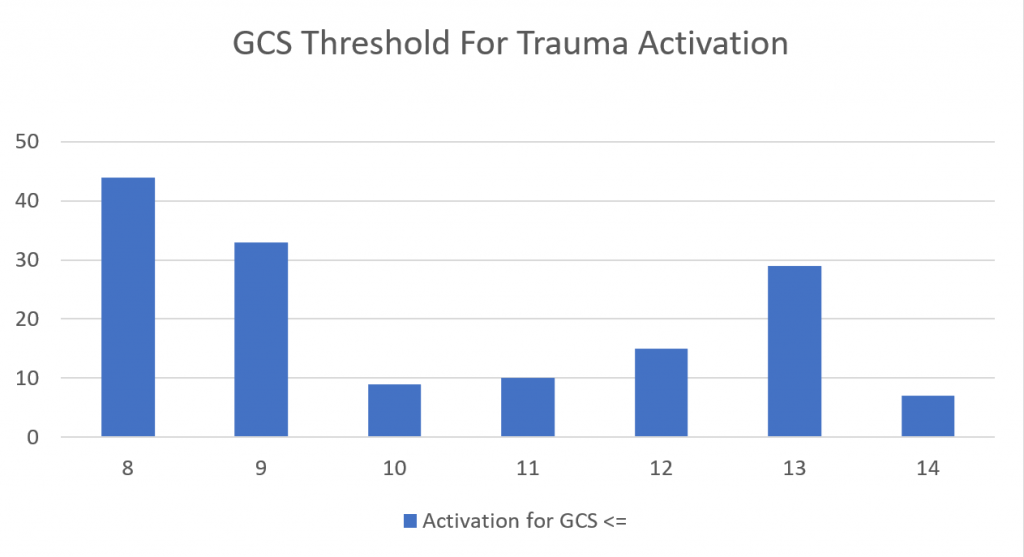

The question was: “What is the highest GCS score that triggers a top-level trauma activation at your trauma center?”

Here is a chart that shows the results. The proper way to read it is “a trauma activation is called if GCS < xx” where xx is the score under the bar in the chart.

The whole point to calling a trauma activation is to have the full trauma team and infrastructure (labs, imaging, blood, etc.) in place to rapidly assess a patient with life-threatening injuries. In theory this should afford them the best probability of survival.

So what is the optimal GCS score to activate your trauma team? Unfortunately, this remains difficult to answer exactly. From the chart, you can see that the most common scores were 8, 9, and 13. Why such a spread?

The GCS 8 and 9 levels are a no-brainer (ha!). These patients are comatose or nearly so, and obviously need prompt attention such as airway control, head CT, and neurosurgical consultation. But what about the patients with GCS 13? They have lost two points, typically for eye-opening and verbal response. This may indeed indicate a significant head injury. But all too often we see this same score in patients who are intoxicated. Do we really need (or want) to activate the full team for each and every intoxicated patient? Can we screen them out in some way?

The answer to both questions is yes. The most important tip is to know your patient population. There is an association between GCS and need for operative intervention that was oft-quoted in the ATLS course. However, I have not been able to find a definitive paper on this topic.

I recommend that you tap into your trauma registry and create a chart that shows presenting GCS vs early neuro-intervention (ICP monitor or craniectomy within 24 hours). Find the GCS score where you see a “significant” bump in the number needing a procedure, and use this as your trauma activation threshold. This report will automatically take into account the number of intoxicated patients you treat.

I would also recommend you do a separate report on age vs need for neuro-intervention with GCS<15. The older population tends to require craniectomy for TBI more often and at higher GCS levels than younger people. You may factor this into your single GCS criterion, or add a separate one at a different level for patients over 55, or 60, or whatever reflects your patient age mix.

Bottom line: Make sure your GCS trauma activation criteria adequately identify your patients who truly have a need for speed in their trauma evaluation. A GCS of 8 or 9 may be too low, and a score in the teens is probably more appropriate for most centers. Use your trauma registry to determine the best score for you so you can capture the patients who have critical needs while trying to keep overtriage under control.