You recently received a trauma activation patient after a high speed car crash. She was restrained with belts and airbags, and really has minimal trauma. There is clinical evidence of a few right-sided rib fractures, and nothing else. She has no significant past medical history, but is overweight to obese. You estimate the BMI as about 31.

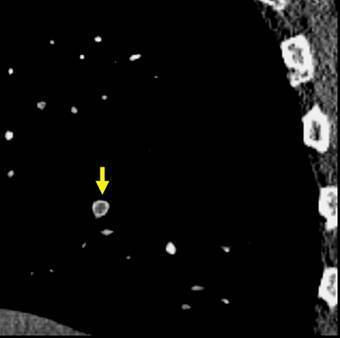

Following your blunt trauma imaging protocol, one of the scans you obtain is a chest CT. It confirms that the aorta has not been injured and shows two rib fractures. After review, the radiologist calls you with a puzzling result. The patient has a small pulmonary embolus seen in a distal (third order) branch of the pulmonary artery in the left lung.

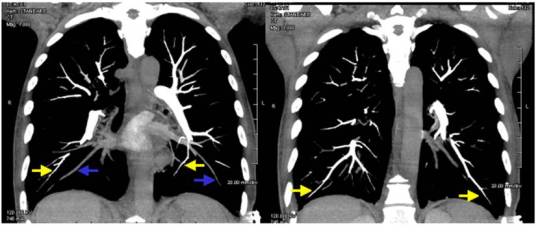

Here’s a coronal view of the scan that you looked at. The arrows show some peripheral branches, but you didn’t see anything on your average resolution monitor.

Here’s a sagittal view in high-rez that the radiologist looked at.

Yup, looks like a pulmonary embolus. Here are my questions:

- Where did it come from?

- What do you do next?

- What type of treatment is needed?

Think this over this weekend. Discussion and answers on Monday.