I hate the pancreas. It just doesn’t play by the rules. No matter how good your operation is, there are frequent complications caused by this organ. Thus, my management recommendations are based on simplicity. Easy stuff is good. No anastomoses are better than one or more.

So you’ve already figured out the location and presence or absence of ductal injury, meaning that you know the grade. Let’s look at what you can do by grade.

- Grade I – somebody rubbed the pancreas. Really, you only need to worry about a little “pancreas sweat”, secretions from roughed up surfaces on the gland. I recommend placing a nice drain in the vicinity to carry this fluid away. This is especially important if there are bowel injuries / anastomoses in nearby areas.

- Grade II – somebody punched the pancreas. This can also be caused by anatomic issues when removing the spleen. Once again, drainage of (non-ductal) secretions is key, so a nice big fat drain is in order.

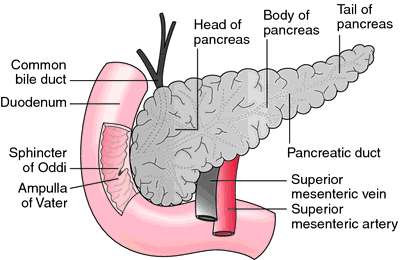

- Grade III – distal duct injury. A simple, distal pancreatectomy is in order. I like to do this with a linear stapler, and I typically do not try to spare the spleen. It just takes too long, and you may push your badly injured trauma patient down the damage control route if you persist with saving the spleen for too long.

- Grade IV – injury to the proximal pancreas with duct. You can get fancy here and do resections and roux-en-y limbs and all kinds of stuff. But I try to keep it simple, and if the destruction is not too bad, I’ll just drain it. External drains are good, but in some more severe cases I will drain internally via a roux limb (shudder). On rare occasion, a proximal pancreatectomy with roux drainage of the distal portion may be considered.

- Grade V – shattered head plus/minus duodenum. Oh crap! The only way out of this is with a pancreaticoduodenectomy, and it’s tough to find a good time with major trauma patients. If they are well-behaved during the initial operation, get started with it. If they are not, or start to have problems during, you can continue to the first damage control takeback. But, to ensure the best quality tissue for anastomoses, you must finish at the first takeback! And expect complications. They always get them.

Friday, I’ll talk about the (foolhardy) idea of trying to treat this injury nonoperatively in children.

Related posts: