Anyone who takes care of blunt trauma has seen the Morel-Lavallee lesion (M-L). Here’s an obvious one because it’s acute:

The M-L lesion is essentially a closed degloving injury in which the skin remains intact. The subcutaneous tissue is sheared off of the underlying fascia, and typically blood accumulates in the potential space that is created. This picture shows a less acute lesion; the bruising and ecchymosis on the surface have resolved. Note the collection on the lateral thigh:

These injuries may take a very long time to resolve and may leave some residual deformity. The definitive management has never been very clear: needle drainage vs incision, timing, compression wraps, etc.

The Mayo Clinic reviewed their 8 year experience with 87 of these lesions to try to shed some light on proper management. They treated their patients in four different ways: needle drainage, incision and drainage, compression wraps, and debridement with vacuum drainage devices. Here are the factoids from their study:

- Motor vehicle crash was the most common etiology for this lesion, which makes sense due to the energy needed to shear the tissues

- The most common locations were thigh, hip and flank

- The incidence of pre-existing conditions that might influence outcome (diabetes, obesity, smoking history, use of anticoagulants) did not seem to influence outcomes

- Lesion location did not change the recurrence rate (even over joints)

- Aspiration suffered the highest recurrence rate (56%) vs only 15-19% in the other groups

- Aspiration of more than 50cc of fluid was more common in lesions that recurred (83%) vs those that did not (33%)

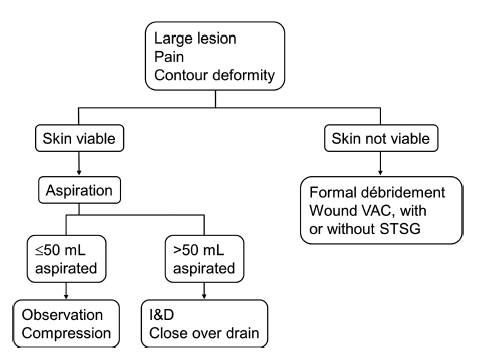

Their experience led them to develop the following practice guideline:

Bottom line: The Morel-Lavallee lesion can be challenging to treat. Although this study has limited numbers, it provides enough guidance to suggest a consistent way of managing it. I recommend adopting this algorithm to provide a standard pathway for dealing with it.

Reference: The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallee lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma 76(2):493-497, 2014.