Here’s another one to test your powers of deduction. The question is not “what’s the diagnosis on this x-ray,” but rather, “what was exact mechanism of injury?”

Hints tomorrow if no one guesses today. Please respond via comments below or Twitter!

Here’s another one to test your powers of deduction. The question is not “what’s the diagnosis on this x-ray,” but rather, “what was exact mechanism of injury?”

Hints tomorrow if no one guesses today. Please respond via comments below or Twitter!

You’re doing one of those (very rare) DPLs and get a surprise result. Not blood, not obvious intestinal content, but just a small amount of mysterious sediment. What to do?

Well, this is obviously not normal. Therefore, this has to be considered a positive diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Since DPL is a qualitative test (meaning that the answer is only yes or no), the patient must go to the OR.

Here are the answers to the questions posed earlier today:

Here’s what I found in this case:

The catheter went straight into the cecum! So we actually did a diagnostic colonic lavage! The sediment was a very small amount of stool. And as stated above, had the catheter not been left in place, it would have been very tough to find the puncture site.

Next, I clamped the catheter to keep it in place, cut it on the hub side, and removed most of it.

Finally, I placed a purse-string stitch around the entry site in the bowel, removed the catheter and tied the suture.

But wait, we’re not done yet! The patient did have abdominal pain and a seat belt sign, so we did a trauma exploration through the midline incision. A Grade II liver injury was present which needed no further management. The patient did well and was discharged on the fourth day.

Bottom line: Procedures can and do go awry. Reason your way through it the best you can, then use focused diagnostics, if needed, to come up with a plan. For misplaced needles and catheters, most organs can tolerate a puncture by almost anything (except the eye, maybe). Treat appropriately and monitor carefully afterwards.

Source: Personal archive. Not treated at Regions Hospital

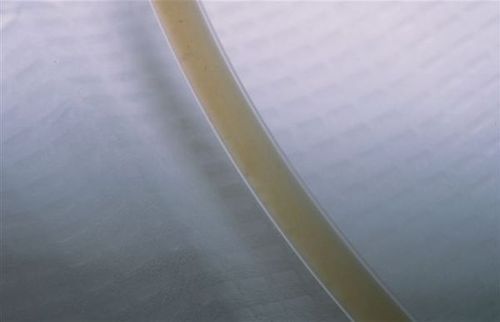

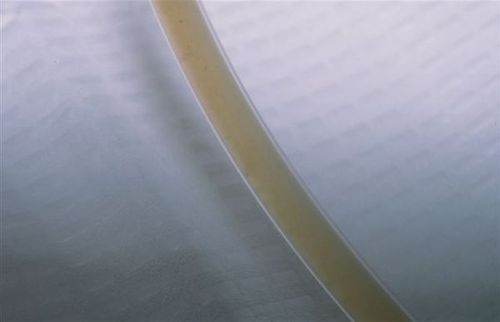

So the catheter is in, the aspirate was negative (nothing came out), and a liter of crystalloid infused easily. But toward the end of draining the fluid back out, some faint sediment became visible in the tubing.

A lot of you guessed bladder, but most people don’t have sediment there. Plus, if I dumped a liter of fluid into your bladder, you’d really get the urge to go. This awake patient noted no new symptoms.

I had a bad feeling about this, so I elected to take her to the OR to see what the story really was. Here are some questions for any budding surgeons out there:

Answers later today! See if you can get it before I give you the punch line!

Ahh, remember the good old days of DPL? Probably not! But here’s an interesting case that presents a real diagnostic dilemma. Hint: this case occurred B.F. (before FAST) and B.G.C.T. (before good CT). That’s why we used DPL!

The patient was a middle aged woman who was involved in a car crash. She had mild, diffuse abdominal pain and a faint seat belt sign. She was prepared for DPL in the ED. It was performed using percutaneous (Seldinger) technique with a fenestrated catheter. Placement was in the usual position, 2cm below the umbilicus in the midline.

The aspirate was negative. A liter of LR was infused and the bag was then lowered to drain. About 600 cc of clear amber fluid returned easily.

However, on closer inspection, a small amount of sediment could be seen in the tubing.

What the heck!? What’s going on and what, if anything, do we need to do?

Post your guesses and comments below, or Tweet them. I’ll provide hints over the weekend, and the answer on Monday.

Source: Personal archive. Not treated at Regions Hospital

Time for the answer! There were lots of well thought out guesses, and a few correct answers.

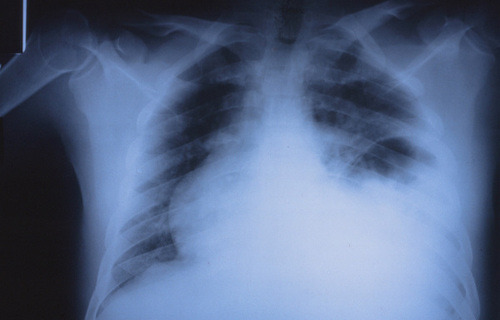

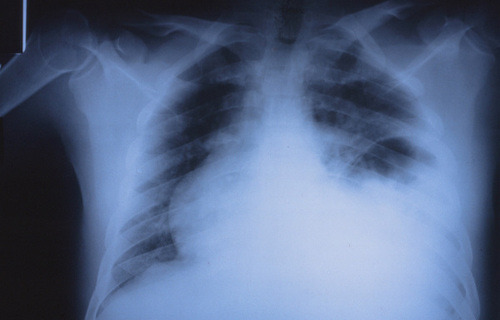

Here’s the story. This is a young male who presented in the trauma room with a small penetrating injury on the lateral aspect of his right arm, and another one just medial to the top of the scapula. If you look at first image last Wednesday, you can see an obvious humeral fracture, a not so obvious lack of lung markings, and a few tiny metallic foreign bodies (bullet fragments picked up by Canuck ER MD, injuries surmised by Kurt Rubach, paramedic). I provided a zoomed in view on Thursday to make them a little more obvious.

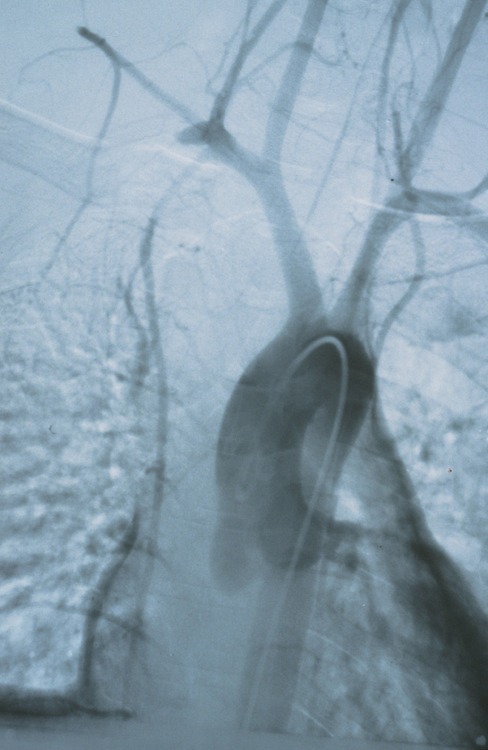

What I didn’t tell you (besides the fact that there were bullet holes) was that there were no pulses in the arm. The patient was hemodynamically stable, so after evaluation in the ED and insertion of a chest tube, he was taken to angio to evaluate the injury location. Unlike many penetrating injuries where the location is obvious, this was a deep mediastinal hit possibly involving Zone I of the neck (thanks Traumahst). Angio was selected because this was in the days before chest CT.

This shows a cutoff of the right subclavian artery. The patient was taken to the OR for sternotomy with a right neck extension and resection of the medial third of the clavicle (see Friday’s xray). The injury was successfully repaired with good return of function, and some residual hemothorax. He was discharged home in a week.

Bottom line: This one was tough because I didn’t give you much of what trauma professionals really need: clinical context. An isolated xray without a clinical history is not enough. It’s very easy to see things that really aren’t there and end up on a wild goose chase. Keep that in mind the next time you expect your radiology colleagues to come up with miracle diagnoses while sitting in a darkened room. Give them the whole story, or have them pop over to the ED to see for themselves.