I’ve previously written about management of extraperitoneal bladder injuries. One of the tenets is that every injury needs to have a routine followup cystogram to ensure healing and allow removal of any bladder catheter. I routinely like to question dogma, so I asked myself, is this really necessary? A retrospective registry review from the Ryder trauma center in Miami helped to answer this question.

Over 20,000 records were screened for bladder injury and 87 were found in living patients. Fifty were intraperitoneal injuries, and half of them were caused by pelvic fractures (interesting). All were operated on, and 47 were classified as simple (dome disruption or through and through penetrating) and 3 were “complex” (involving trigone). All trackable patients (42 of the 50) had followup cystograms 9-16 days later. All of the simple injuries had a normal followup exam, but a leak was detected on one of the complex injuries.

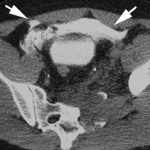

There were 42 patients with extraperitoneal bladder injuries. All were due to blunt trauma, and 92% were associated with pelvic fractures. Most were found with CT cystogram. Two patients had operative repair, probably due to the need to fix the pubic bones with hardware. 37 of the 42 were available for followup, and 22% of repeat cystograms were positive (average study done on day 9). In the studies that showed a leak, repeat cystograms were done, and they took an average of 47 days to fully heal.

Bottom line: Patients with extraperitoneal or complex intraperitoneal bladder injuries (trigone) really do need a followup cystogram before removing the bladder catheter. Those who underwent a simple repair of their intraperitoneal injury do not.

Related posts:

Reference: Cystogram follow-up in the management of traumatic bladder disruption. J Trauma 60(1):23-28, 2006.