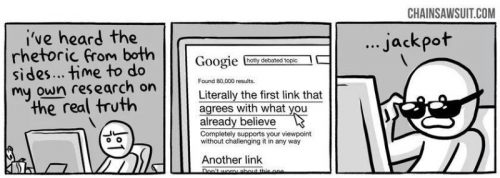

The veracity of medical research conclusions, specifically trauma research, has always fascinated me. I see so many people who are content to jump to conclusions based on a paper’s title or the conclusions listed in its abstract. However, having read thousands of research papers over the years, I am no longer surprised when these easy-to-digest blurbs don’t entirely match up with the actual details embedded within the manuscript.

The authors of these publications genuinely intend to provide new and valuable information, either for clinical use or to allow future studies to build upon. Unfortunately, mistakes can be made that degrade their value. Problems with research design are among the top culprits that affect the significance of these papers.

I will focus on what are considered “gold standard” studies in this post. The randomized, controlled trial (RCT) is usually considered the big kahuna among research designs. They can provide solid answers to our clinical questions if designed and carried out properly.

In 2010, a checklist of 25 guidelines was created (CONSORT 2010, see reference 1) to guide researchers on the essential items that should be included in all RCTs to ensure high-quality results. A group of investigators from Jackson Memorial in Miami and Denver Health published a paper earlier this month that critically reviewed 187 trauma surgery RCTs published from 2000 to 2021. They analyzed power calculations, adherence to the CONSORT guidelines, and an interesting metric called the fragility index.

Here is a summary of their findings:

- Only 46% of studies calculated the sample size needed to prove their thesis before beginning data collection. With no pre-defined stop point, the researchers might never be able to demonstrate significant results or may be wasting money on subjects in excess of the number actually needed.

- Of the 54% that did calculate the needed sample size, two-thirds did not achieve it and were not powered to identify even very large effects. Once again, they are spending research money and will almost certainly be unable to show statistical differences between the groups, even if one actually existed.

- The CONSORT checklist was applied to studies published after they were developed in 2010; the average number of criteria met was 20/25, and only 11% met all 25 criteria. The most common issue was failure to publish the randomization scheme to ensure no bias was possible due to it.

- Among 30 studies that had a statistically significant binary outcome, the mean fragility index was 2. In half of these studies, having a different outcome in as few as two patients could swing the final results and conclusion of the study.

- The majority of the studies (76%) were single-center trials. Frequently, such trial results cannot be generalized to larger and more disparate populations. Larger, confirmatory studies often have results that are at odds with the single-center ones.

Bottom line: What does it all mean? Basically, a lot of well-intentioned but poorly designed research gets published. The sheer volume of it and the work needed to interpret it correctly make it very difficult for the average trauma professional to understand and apply. And unfortunately, there is a lot of pressure to pump out publication volume and not necessarily quality.

My advice for researchers is to ensure you have access to good research infrastructure, including experts in study design and statistical analysis. Resist the temptation to write up that limited registry review from only your center. Go for bigger numbers and better analysis so your contribution to the research literature is a meaningful one!

References:

- CONSORT 2010 Guidelines Checklist for randomized, controlled trials

- Statistical Power of Randomized Controlled Trials in Trauma Surgery. JACS 237(5):731-736, 2023.