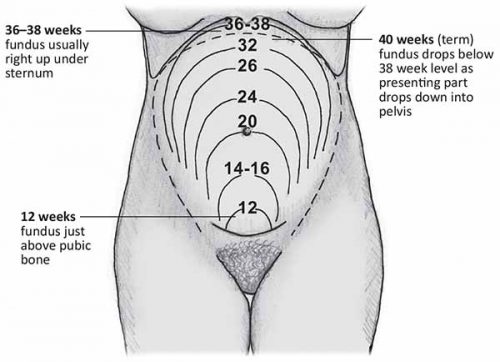

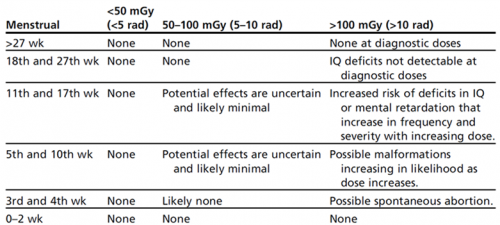

Everyone worries about imaging pregnant patients. As with most medical tests, it always boils down to risks vs benefits. What are the chances of causing mutations or cancers or a spontaneous abortion, and what is the risk of missing a critical injury? In general, reasonable studies involving a fetus at just about any point in gestation won’t cause major problems. At least as far as we know. What is not clear are the longer term, hard to measure effects. So the general philosophy should be to order just what you absolutely need, and shield the fetus during any studies other than of the abdomen/pelvis.

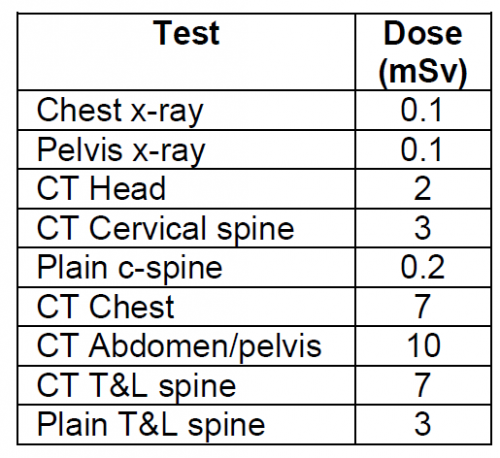

Now, to put these numbers into perspective, have a look at this list of delivered doses from common studies. The table above is listed in milliGrays, and this one is in milliSieverts. These are roughly comparable, except that the former is a measure of radiation dose absorbed, and the latter measures radiation delivered.

Bottom line: Think hard about the imaging you really need. If you generally do this for all patients, you probably won’t change your practice in pregnant women. Don’t worry about chest and pelvic x-rays. Shield the fetus for anything not involving the abdomen/pelvis. For major torso trauma, you probably will need CT of the chest/abdomen/pelvis. If so, do it right. Order with contrast so you don’t get substandard images that need to be repeated.