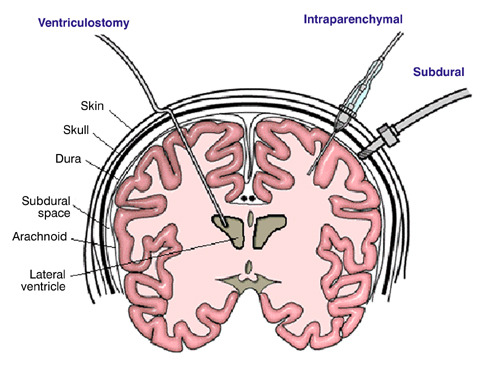

There is some variability in how neurosurgeons manage ventriculostomy when it comes to antibiotic coverage. The catheter can become a conduit for bacterial infections of the meninges or brain, which can be life threatening. Most neurosurgeons will begin coverage at the time of catheter insertion, but the duration of treatment varies. What is the right answer, if any?

As is typical with most things related to head trauma, there are not a lot of good studies out there. Columbia University published a fairly comprehensive review of previous studies last year to help clarify this issue. They applied rigorous criteria to identify 10 relevant studies (3 randomized clinical trials and 7 observational studies) out of a pool of 347. Yes folks, this gives you an idea of how tough it is to answer good clinical questions from the stuff that gets published.

The study found that the use of either prophylactic antibiotics or antibiotic-coated external ventricular drains (EVD) decreased the number of infections by 68%. This result was consistent across both study designs. The authors could not show that one mode of antibiotic administration (systemic vs catheter coating) was better than the other. About half of the studies used antibiotics for the duration of the catheter; the other half did not specify.

Bottom line: Head injury patients with an EVD should receive antibiotics, either systemically or as a coating on the EVD catheter itself. Although not entirely clear, they should probably be given for the entire time the catheter is in place. Judgment must be used if this will be a long time, because there may be other adverse effects from giving long term antibiotics.

Reference: Prevention of Ventriculostomy-Related Infections With Prophylactic Antibiotics and Antibiotic-Coated External Ventricular Drains: A Systematic Review. Neurosurgery 68(4):996-1005, 2011.