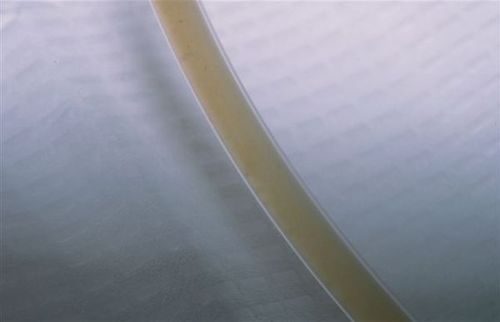

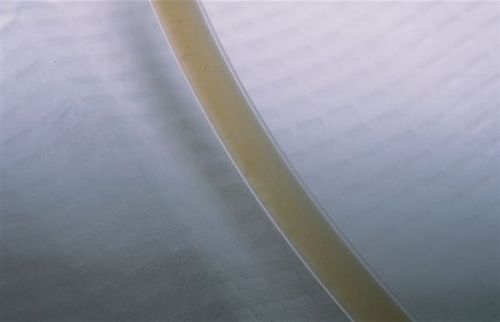

The patient underwent DPL and had an abnormal result, with weird sediment in the tubing.

Since this is, by definition, a positive result, they were taken to the OR. The DPL catheter was left in place to help localize what was going on. This is particularly helpful if an iatrogenic injury to a hollow organ is suspected. Otherwise it may be very difficult to find a tiny puncture wound.

It turns out that the catheter made a beeline for the cecum, resulting in a DCL (diagnostic colonic lavage), not a DPL. The particulate material was stool!

Since the catheter had been left in place, there was no contamination. It was removed under direct vision and a single stitch was placed to close the defect. Finally, a formal exploration was carried out to find the source of the patient’s abdominal pain. A low grade liver laceration was found that did not need any specific therapy. The ultimate source of her initial hypotension? Multiple long bone fractures with attendant bleeding into soft tissue. The abdomen was closed and the patient did well after fixation of her fractures.

It pays to know a little bit about DPL, even though it is seldom used these days. It can be useful, particularly when trying to rule the abdomen in or out as a source of bleeding where FAST is unavailable, indeterminate, or the result is suspect.

Check out this post for some tips and tricks on DPL: