I’ve been fascinated by 3D printing for at least a decade. Here are some examples from previous posts:

- Planning orthopedic surgery using a 3D printer

- A 3D Bioprinter For Skin

- The Aether Bioprinter prints bone and cartilage (video)

Unfortunately, practical applications have been relatively limited in the field of trauma. But a lot has been going on in the background. The trauma research group at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam recently published a systematic review on very practical work using 3D printing to produce casts and splints.

Sounds like a very mundane problem to through high tech at, right? But for those of you who look after patients with fractures that have been casted, you know the problems that can arise. Casts can be too tight. They can be ill-fitting. The patient may have soft tissue injuries that require windows cut into the side of the cast. Additional technology such as electrical stimulators may be indicated to enhance healing.

The old-fashioned way of creating a plaster or fiberglass cast seems crude. It is shaped by hand using skill and a fair amount of guesswork. If it’s just a bit too tight, serious complications may occur. If windows are not cut properly, it can destabilize the entire cast.

The Rotterdam trauma research group performed a systematic review of 12 papers that have been published on the topic of 3D-printed casts used in the treatment of forearm fractures. The authors found that most currently use a technique called fused deposition modeling with a polylactic acid substrate.

Instead of relying on subjective skill and luck to shape the brace, the uninjured forearm is scanned with a 3D scanner. The data is fed to a computer aided design (CAD) workstation and a mirror image is created and further refined. Special features such as soft tissue windows or entry points for bone stimulators can be designed into the brace at that time. Because the strength of polycarbonate exceeds that of plaster and fiberglass, it is possible to create a design with a great deal of open area so the underlying skin can be monitored. And allowances can be made for areas with swelling not present on the control extremity.

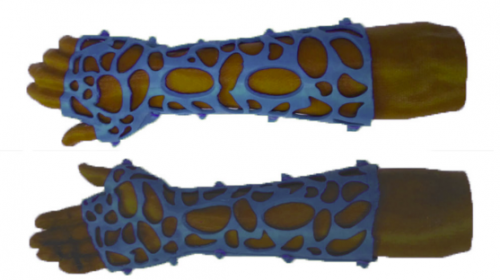

The data is then fed to a 3D printer to actually create the cast. Here’s an example:

This design is stronger that a traditional cast, is cool and comfortable, and avoids problems with hidden tissue injury or unrecognized foreign objects dropping into the cast creating major problems.

The use of 3D-printed casts and braces is relatively new and is used in only a few centers. For this reason, we do not have enough numbers to show that it is equivalent to traditional casting. Yet. But as the price continues to drop and use becomes more widespread, it’s only a matter of time before you start seeing these items in your own trauma center.

Reference: Personalize d 3D-printed forearm braces as an alternative for a traditional plaster cast or splint; A systematic review. Injury, in press, July 29, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2022.07.020