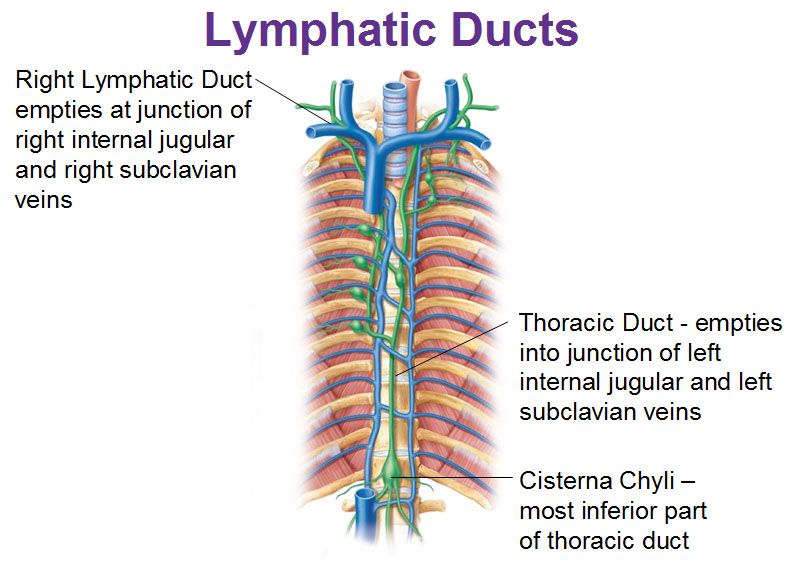

Today I’m going to review a very uncommon clinical problem in trauma: injury to the thoracic duct. To review, the lymphatic system coalesces into channels along the spine. These vessels travel upwards to drain into the venous system as the left and right lymphatic ducts. The exact drainage points vary, but are near the junctions of the internal jugular and subclavian veins bilaterally. Technically the larger of the two, the left lymphatic duct, is termed the thoracic duct. However, injuries can occur on either side.

Injuries to the lymphatic ducts are very rare due to their small size and their protection by surrounding structures and tissues. For this reason, the literature on this topic consists almost exclusively of case reports. Injury can occur from direct penetration by gunshots or stabs, or may be associated with high energy blunt trauma. It has also been reported to occur in cases of multiple posterior rib fractures and vertebral fractures.

In the rare event that these ducts are damaged, they pose a major management problem because lymph does not clot. These vessels are not self-sealing like most others in the body. They will only close through healing (scarring) or by ligation. The typical disruption occurs near the junction of the duct with the venous system, so lymph (chyle) typically accumulates in the thorax on the affected side. This results in a hydrothorax until the patient begins eating, when it turns chylous and makes the diagnosis easy. Here a various shades of chyle that you might see in the chest tube drainage.

If in doubt, triglyceride levels can be measured, and a value greater than 110 mg/dL is considered positive.

Initial management is usually dietary, via reduction in fat intake to render the drainage clear. This may be accomplished by a low fat diet or by TPN. I don’t really buy the effectiveness of this, since the fat content is not what causes the leak to persist. It merely makes it unusual to look at. I suspect that the 1-2 week period that most recommend for dietary treatment just provides an opportunity for normal healing/scarring to occur. Octreotide should be given as well because it may decrease overall lymphatic output. Lower output accelerates closure because the amount of scarring needed to close the smaller hole is less.

Interventional radiologists have attempted embolization and needle maceration of the ducts, but the few of these described have been unsuccessful. This is not recommended.

If closure is not achieved in two weeks, then consideration should be given to surgical ligation of the leaking duct. This structure is small and thin-walled, and not the easiest to see. Fats should be administered via NG (olive oil and cream have been described) at the start of the operation to stimulate chyle production. This allows easier identification of the leak site intraoperatively. Suture ligation, clipping, or both can be used to stop the leak.

References:

- A case of a traumatic chyle leak following an acute thoracic spine injury: successful resolution with strict dietary manipulation. World J Emerg Surg 6:10, 2011.

- Blunt rupture of the thoracic duct after severe thoracic trauma. J Trauma Open 3:e000183. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2018-000183m 2018.

- Bilateral Chylhotorax after Falling from Height. Case Reports in Surg article 618708, 2014.