As discussed in my first post in this series, the original Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was described in 1974. It was originally intended to be a chart of all three components, trended over time. Ultimately, the three values for eye opening, verbal, and motor responses were combined into a single score ranging from 3-15. This combined score has become the main focus of our attention, with less interest in the individual components.

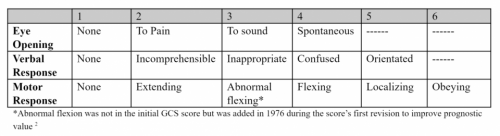

Here is the original GCS:

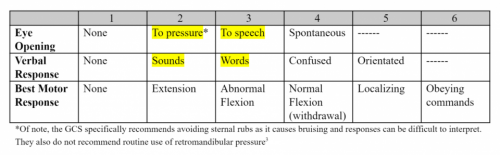

Forty years later (2014), there was interest in tweaking it to overcome a few of the perceived shortcomings. Two relatively small changes were made. First, a few terminology changes were made in the eye opening and verbal response components. Eye opening was clarified to indicate opening to pressure, not pain, and speech, not sound. Verbal response was also clarified, changing “incomprehensible” to “sounds”, and “inappropriate” to “words.”

Additionally, when eye opening or verbal response could not be tested (swelling, intubation), the value was scored as a 1. This was changed in 2014, so that the non-testable components are now marked “NT” and the total score should not be calculated. Here’s an example:

- Original GCS: E1 V1T M3 = 5T

- GCS-40: E1 V-NT M3 (no total)

Here’s the new GCS-40 description published in 2014:

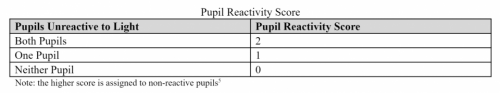

Finally, this year Teasdale and associates added one final tweak. They incorporated an indicator of pupillary response. This table shows the levels of response:

This factor is subtracted from the GCS-40, now resulting in score that can range from 1-15. Addition of this component greatly improves our ability to predict outcome.

Why does all this matter? One important reason is that the American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program will begin accepting data in 2019 with GCS 40 data. The National Trauma Databank data definitions will also incorporate GCS 40 in next tear. It looks like there will be a phase-in period where either system can be used. I could not find any indication that the pupillary score would be included any time soon.

I’m sure research will continue on this staple of trauma evaluation. Expect more tweaks in the future as we try to improve our ability to follow our patients clinically and predict how well they will do.