Yesterday, I reviewed a paper that highlighted a single-institution experience for IVC filter usage. Today, let’s look at a much larger pool of data.

Placement of a filter in the inferior vena cava (IVC) is one of the many tools for managing pulmonary embolism. There was a significant increase in filter placement during the 1990s and 2000s due to a broadening of the indications for its use. There has been continuing debate over the complications and efficacy of use of this device.

A paper from NYU Langone Health in New York City, the Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute, and Georgia Institute of Technology School of Economics looked a long-term trends in IVC filter use in the Medicare population. They scanned a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) database over the 22 year period from 1994 to 2015. They specifically analyzed trends in insertion, removal, placement setting, and specialty of the inserting physician.

Here are the factoids:

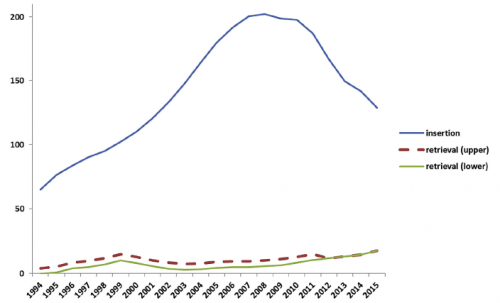

- 2008 seemed to be the heyday of IVC filter insertion. Rates nearly tripled by 2008, but have declined about 40% since then (see below). Pay attention to the retrieval rates.

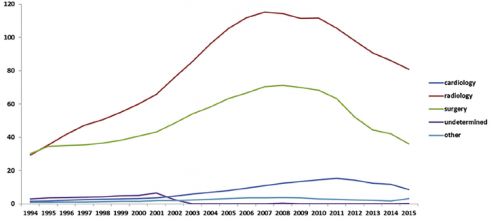

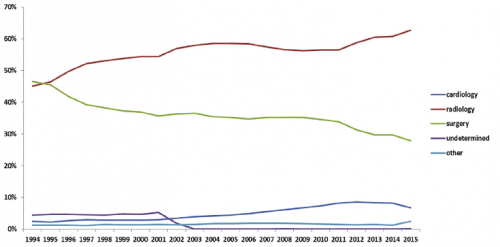

- Overall, filters were most commonly placed by radiologists, followed by surgeons and cardiologists. Here’s the diagram above broken down by specialty.

- This chart shows the market share of each specialists inserting IVC filters during the study period. Of note, radiologists continue to increase and surgeons are decreasing.

Bottom line: This study shows some interesting data, but can’t be completely applied to trauma patients because it focuses on Medicare recipients. But the trends are valid. IVC filter use peaked in 2008 and has been declining ever since. Radiologists place more filters than other specialties, and their market share continues to increase.

Most disturbing is the low filter retrieval rate, similar to what was seen in yesterday’s post. Device manufacturers recommend removal of most filters, but timeframes are not specified. The real bottom line is that we have an indwelling device which works well in very limited situations only, can cause long term complications, and that we frequently forget to remove. It behooves all trauma professionals to develop strict guidelines for both use and removal.

Reference: National Trends in Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement and Retrieval Procedures in the Medicare Population Over Two Decades. J Am Coll Radiol 15:1080-1086, 2018.