Compartment syndromes can occur virtually anywhere a muscle group is surrounded by relatively unforgiving soft tissue. In trauma, these classically involve the calf, forearm, and occasionally the thigh compartments. But they are occur unsuspected in the less common areas they can easily be missed, leading to significant morbidity, disability, and even death.

The gluteal compartment syndrome is one of those uncommon occurrences. Actually, it’s extremely rare, with less than 50 cases documented in the English literature. It is typically seen in patients who are impaired in some manner (drugs, alcohol, stroke) and are unable to move. If they lie in such a way that significant pressure is exerted on the buttock, the full syndrome can develop.

Typical symptoms include swelling, firmness, and pain in the buttock. Neurologic findings are fairly common. Paresthesias can develop late, and pressure on the sciatic nerve can ultimately begin to cause a sciatic palsy.

As with most compartment syndromes, the diagnosis is usually made solely on physical exam. However, in patients with more body fat it may not be as apparent. A pressure monitor can be inserted directly into the fleshiest part of the buttock, and elevated pressures (approaching or exceeding 30 torr) clinches the diagnosis.

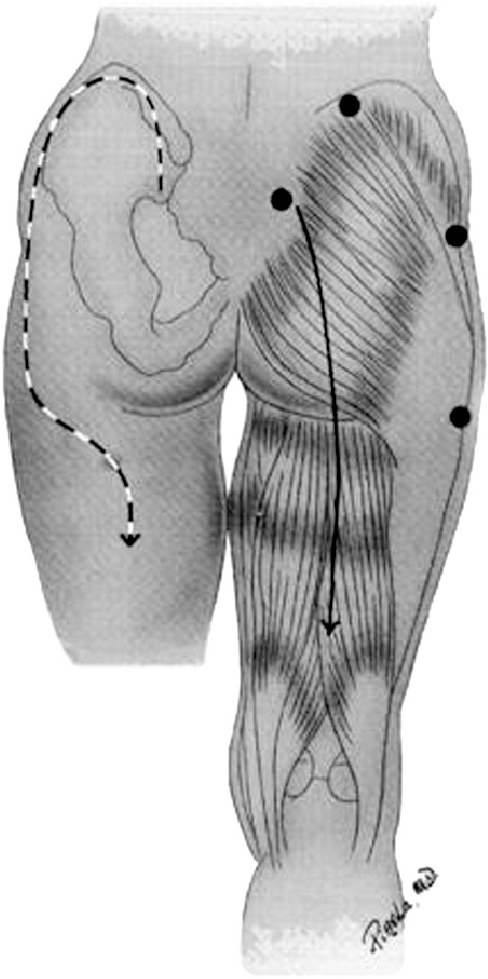

The mainstays of treatment are surgical release and physiologic support, primarily for rhabdomyolysis and secondary renal injury. There are two types of incision that may be used. The classic straight line, shown on the right below, is simple but significantly disfiguring. The question mark incision on the left is kinder and gentler, but more challenging to perform properly.

Bottom line: Compartment syndromes can occur in any enclosed muscle group, which is just about all of them. Always be suspicious if your patient has unexplained elevations of CK, especially if they have tight muscle groups or deep pain in hard to access muscles. Err on the side of checking pressures and releasing those compartments in order to minimize morbidity and ultimate disability.

Reference: Gluteal compartment syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2:190, 2009.