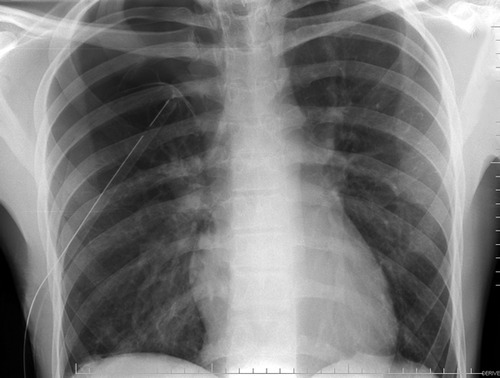

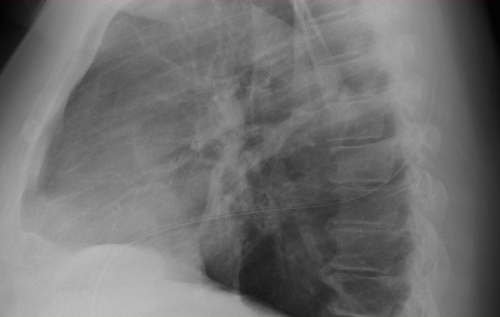

More dogma, or is it actually useful? Any time a chest tube (tube thoracostomy) is inserted, we automatically order a chest x-ray. Even the ATLS course recommends obtaining an image after placement. But anything we do “automatically” is grounds for critical analysis to see if there is a valid reason for doing it.

A South African group looked at the utility of this practice retrospectively in 1004 of their patients. They place 1042 tubes. Here are the factoids:

- Patients were included if they had at least one chest x-ray obtained after insertion

- Patients were grouped as follows: Group A (10%) had the tube inserted on clinical grounds with no pre-insertion x-ray (e.g. tension pneumothorax). Group B (19%) had a chest x-ray before and had ongoing clinical concerns after insertion. Group C (71%) had a chest-xray before and no ongoing concerns.

- 75% of injuries were penetrating (75% stab, 25% GSW), 25% were blunt

- Group A (insertion with pre-x-ray): 9% had post-insertion findings that prompted a management change (kinked, not inserted far enough)

- Group B (ongoing clinical concerns): 58% required a management change based on the post-x-ray. 33% were subcutaneous or not inserted far enough (!!)

- Group C (no ongoing clinical concerns): 32 of 710 (5%) required a management change, usually because the tube was too deep

The authors concluded that if there are no clinical concerns (tube functioning, no clinical symptoms) after insertion, then a chest x-ray is not necessary.

Bottom line: But I disagree with the authors! Even with no obvious clinical concerns, the tube may not be functioning for a variety of reasons. Hopefully, this fact would then be discovered the next day when another x-ray is obtained. But this delays the usual progression toward removing the tube promptly by at least one day. It increases hospital stay, as well as the likelihood of infection or other hospital-associated complication. A chest x-ray is cheap compared to a day in the hospital, which would potentially happen in 5% of these patients. I recommend that we continue to obtain a simple one-view chest x-ray after tube insertion.

Related posts:

- What percent pneumothorax is it?

- Don’t get lateral x-rays for pneumothorax diagnosis

- Chest tube tips

Reference: What is the yield of routine chest radiography following tube thoracostomy for trauma? Injury 46(1):45-48, 2015.