We know that even a brief shock episode in patients with severe TBI dramatically increases mortality. Therefore, standard practice is to ensure good oxygenation with supplemental O2 and an adequate airway ASAP and to guard against hypotension with crystalloids and blood if needed.

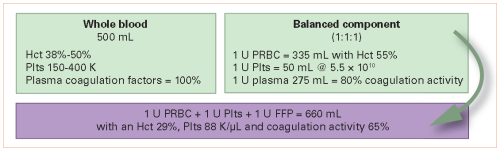

Many papers (and several abstracts in this bunch) have been written about the benefits of whole blood transfusion. The group at the University of Texas in Houston compiled a prospective database of their experience with emergency release blood product usage in patients with hemorrhagic shock.

They massaged this database, analyzing a subset of patients with severe TBI, defined as AIS Head of 3. They specifically looked at mortality and outcome differences between those who received whole blood and those who received component therapy.

Here are the factoids:

- A total of 564 patients met the TBI + shock criteria, and 341 (60%) received whole blood

- Patients receiving whole blood had higher ISS (34 vs. 29), lower blood pressure (104 vs. 118), and higher lactate (4.3 vs. 3.6), all indicators of more severe injury

- Initial univariate analysis did not identify any mortality difference, but using a weighted multivariate model teased out decreases in overall mortality, death from the TBI, and blood product usage

- Neither statistical model demonstrated any difference in discharge disposition of ventilator days

The authors concluded that whole blood transfusion in patients with both hemorrhagic shock and TBI was associated with decreased mortality and blood product utilization.

Bottom line: This is yet another study trying to tease out the benefits of giving whole blood. The results are intriguing and show an association between whole blood use and survival. But remember, this type of study does not establish causality. It’s not possible to rule out other variables that were not available or not considered that could be the cause of the difference.

In this type of study, it’s essential to look at the design. Was it possible to create the study to record a complete set of variables that the researchers thought might contribute to the outcomes? Or is it a retrospective analysis of someone else’s data that contains just a few of them? This study falls into the latter category, so we have fewer data elements to work with and the likelihood that others that are not present could contribute to the outcomes.

The details of the multivariate analysis are also important. The authors stated that weighted multivariate analyses were performed. It’s not possible to provide details in a standard abstract, but these will be important for the audience to understand.

Here are my questions and comments for the presenter/authors:

- Tell us more about the database you used for the analysis. What was the purpose? How many data elements did you collect, and how are they related to your research questions?

- How did you decide which variables to include in your multivariate analysis? And how did you determine the weights? These can have a significant effect on your results.

- This is a preliminary proof of idea study. How should this be followed up to move from association to causation?

This is just one of many exciting studies trying to shed light on the forgotten benefits of whole blood in trauma. I’m looking forward to seeing the final manuscript!

Reference: PATIENTS WITH BOTH TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY AND HEMORRHAGIC SHOCK BENEFIT FROM RESUSCITATION WITH WHOLE BLOOD. EAST 2023 Podium paper #2.