There is considerable variability in the way that penetrating wounds are approached. Some are located over areas of lesser importance (distal extremities) or are so superficial that they obviously don’t fully penetrate the skin.

Unfortunately, some involve high-value structures (much of the neck and torso), or are too small to tell if they penetrate (ice pick injury). How should these injuries be approached?

Too often, someone just probes the wound and makes a pronouncement based on that assessment. Unfortunately, there are major problems with this technique:

- The tract may be too small to appreciate with a finger or even a cotton-tip swab

- The tract may be oriented in an unexpected direction, or the soft tissues may have moved after the penetration occurred. In this case, the examiner may not appreciate any significant depth to the wound.

- Inserting an object may violate a structure that you wish it hadn’t (resulting in a hissing sound after probing a chest wound, or a column of blood after probing the neck)

A better way to approach these wounds is as follows:

- Is the patient unstable? If so, you know the penetration caused the problem and the patient belongs in the OR.

- Is there other evidence of deep injury, such as peritonitis with a penetrating abdominal wound? If so, the patient still needs to go to the OR.

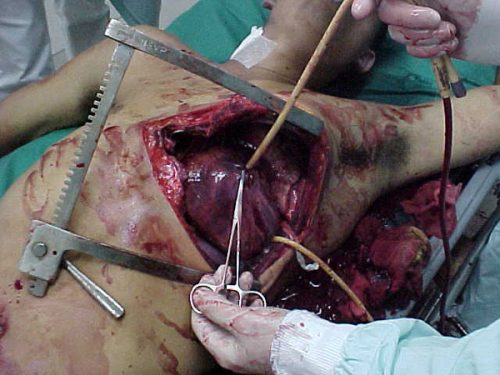

- Do a legitimate local wound exploration. This entails making the hole bigger with a knife, and using surgical instruments and your eyes to find the bottom of the tract. Obviously, there are some parts of the body where this cannot be done, such as the face, but they probably don’t need this kind of workup anyway.

As one of my mentors, John Weigelt, used to say, “Doctor, do you have an eye on the end of your finger?” In general, don’t use anything that doesn’t involve an eyeball in your local wound explorations!