When is the last time this has happened to you? You are called to the ED for a trauma activation. The patient was involved in a motorcycle crash and is doing fine, but he has a large midline scar on his abdomen. You inquire as to what it is. He tells you that he had been involved in another motorcycle crash about five years ago and needed an operation. When questioned about what his injuries were and what was done, he has no idea.

This is an example of health (il)literacy at its best. An earlier study from the Presley trauma center in Memphis demonstrated that less than half of their trauma patients could correctly recall their injuries or their operations.

This is not really surprising. Have you ever taken a minute to look at the sheaf of paper given to hospital patients when they are discharged? They are usually computer-generated gobbledygook and are not easily understood by any human on this earth. It is hard enough to figure out the discharge medications and followup visits. And any diagnosis or surgical procedure information is never in patient-friendly language.

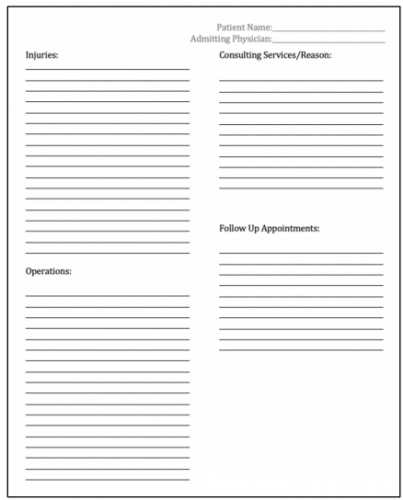

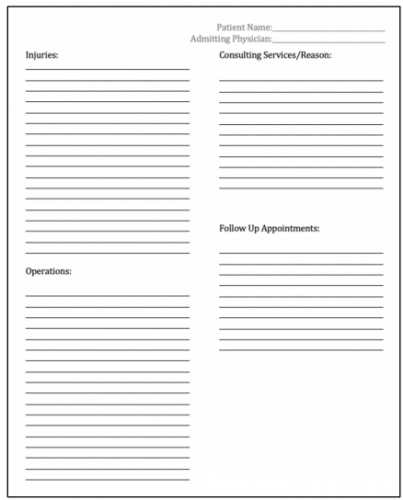

The Memphis group designed a simple discharge information form to provide to their patients:

Here are the factoids:

- Patients admitted to the trauma service over a 6-month period were studied and surveyed during their first post-discharge clinic visit

- A total of 153 surveys were distributed, asking about income, education, and patient satisfaction and their understanding of what happened to them; 146 were returned

- Income levels were low, with about 60% of them less than $25K and 85% less than $50K

- About 75% had a high school education or less

- Implementation of the form increased injury recall some or all of patient injuries from 55% to 85%, and recall of operations from 43% to 76%

- The number of patients who could recall any of their providers’ names increased from 11% to 31% (!)

- Injury understanding, satisfaction with injury understanding, and the overall impact on hospitalization was significantly positive

The authors concluded that introducing this simple form dramatically improved their patients’ health literacy, and their patients were able to provide more details to providers they visited post-discharge.

Here are my comments: I think the bottom line here is to know your patients! Socioeconomic and education status vary dramatically by geographic location. This certainly has an impact on the understanding and recall of hospital events by our patients. It can help us optimize processes to provide meaningful and important information that they need to know in the future.

The form used in this study was very simple, consisting of a series of blanks to be filled in by a healthcare provider. But who was this provider? All medical professionals tend to use the lingo that we learned in training. But our patients have zero understanding of them. Consider the lowly Foley catheter. Tell a patient you are going to insert one, and they will say “uh-huh.” But tell them that you are preparing to stick a big rubber tube in their penis, and the response will be much more vocal. Make sure the language is simple and lingo-free.

The recall of provider names improved only modestly. This may be due to the typical “interchangeable head” model where the various healthcare professionals change on a frequent bases. Additionally, patients are seen by a horde of nurses, physicians, APPs, residents, techs, and others during their stay so it’s easy to forget a name.

Overall, the results were very promising. This is a significant advance in patient health education and literacy. I think the next step is to provide a library of information sheets based on the common injury diagnoses and operations that occur at the trauma center. This, coupled with a more intelligible set of discharge papers in general will be of great help to our patients.

Here are my questions for the presenter and authors:

- Why so few surveys? Your center is very busy, and the study data only involved about 25 patients per month. How did you select them, and might information obtained from all the other patients have changed your results?

- Did you independently review the discharge forms to ensure understandable language? The intelligibility could vary significantly based on the provider filling it out.

- How did your care model affect the patient recall of their providers? Do your residents or attending surgeons rotate on a frequent basis? What other factors might have influenced this?

- What next? How has this information changed how you educate your patients now? What additional changes might you make in the future? How will you roll it out to more than just 25 patients per month?

This is excellent work! I’m looking forward to your live presentation later this week.