Just like children are not small adults, elderly patients are not just old adults. As I mentioned yesterday, mortality increases significantly as we get older such that the same injury is much more likely to kill an elder.

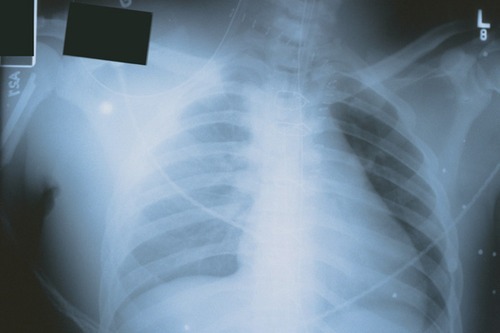

Rib fractures are no exception. A 10 year retrospective cohort study looked at the management and mortality of this problem in patients 65 and older at Harborview in Seattle. When comparing young and old patients with the same number of fractures and injury severity, death and pneumonia were twice as likely in the elderly (22% vs 10% mortality, 31% vs 17% pneumonia). Ventilator days and hospital/ICU length of stay was significantly longer, too. Mortality increased by 19% and pneumonia increased by 27% for each additional rib fracture in the elderly.

Here are some practical tips for management of rib fractures in the elderly:

- Admit any older patient with even a single rib fracture for pain management and pulmonary toilet

- Treat their pain well, but watch the narcotics! Consider an epidural if indicated, but monitor carefully.

- Keep your patient out of bed as much as possible. Chairs are good, walking is better.

- Encourage coughing and other pulmonary toilet techniques

- Do not discharge until they pass the “eyeball” test. This means that they have to look well enough to go home and participate in their usual activities. They should be walking around at their usual speed and agility. It does no good to discharge and lay in bed or on the couch. They’ll be back dying of pneumonia before you know it.

- A general rule of thumb: Length of stay is generally n+1 days, where n is the number of rib fractures (isolated injury). Be wary of trying to send someone home sooner than this.

Related posts:

- Thoughts on geriatric trauma

- Rib fracture management

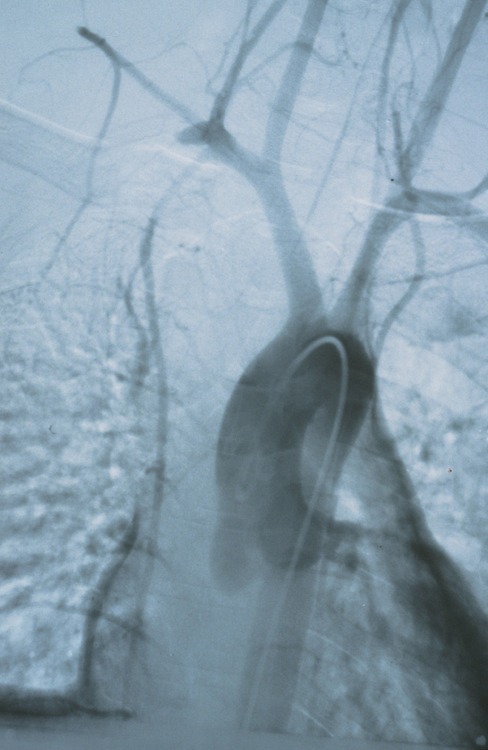

- Trauma 20 years ago: continuous epidural analgesia for rib fractures

Reference: Rib fractures in the elderly. J Trauma 48(6):1040-1046, 2000.

Thanks to Scott Weingart, author of the EMCrit Blog (www.emcrit.org) for suggesting this topic!