First, I would like to state that REBOA is not for the faint of heart. Hmm, not a very good idiom. It actually might be, if you are the patient.

I say this because REBOA has a definite learning curve from a technical standpoint. But it does use standard trauma and vascular surgical techniques, which makes it a little easier to grasp. At this point, it should primarily be performed by surgeons, since it frequently creates a vascular injury that requires surgical repair at the end of the procedure. However, to be fair, emergency physicians can and do initiate the procedure here and in some countries outside the US, such as Japan. Terminating it is another matter.

From a patient selection standpoint, think of it as a way of keeping your patient alive until you can get them to the OR for definitive control of their hemorrhage. You are trading 5 to 10 more minutes in the trauma bay inserting it for a (potentially) safer trip to the OR suite, and lets the surgeons start the case with some modicum of vascular control already in place.

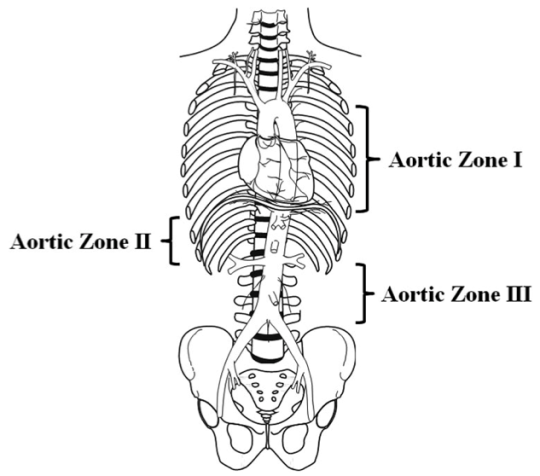

The abdomen is divided into 3 REBOA zones, depending on where the hemorrhage is located. Here’s the map:

For bleeding in the abdominal cavity, the REBOA balloon is placed in Zone I. For practical purposes, we try to occlude the distal aorta at the diaphragm, where we would normally place the crossclamp for an ED thoracotomy.

For pelvic bleeding, generally from branches of the iliac arteries, the balloon is placed in the distal aorta, Zone III. Zone II is not used currently.

So who will benefit from REBOA? The answers to this question are still being teased out of the small series that are being produced by a number of centers. The general rule is that any patient with exsanguinating hemorrhage originating below the diaphragm should be considered for this procedure.

Does that mean all patients? Patients who still have vital signs? How good or bad do they need to be? Unfortunately, we don’t know yet. But we are working on it.

Monday: How is REBOA performed?

Direct links to the REBOA series: