As all trauma professionals know, traumatic injuries are a major cause of death across all age groups. Well-trained trauma teams use all their skills to attempt to save critically injured patients. But, unfortunately, there are occasions in which they die despite all our efforts. In most of these cases, the time of death is called, and team members then peel off their protective clothing and melt away to pursue their usual duties.

These terminal trauma activations are mentally challenging as the proper interventions are ordered and carried out. They are also physically demanding, especially when heroic measures such as CPR are needed. But one often-neglected issue is the emotional challenge. Every team member is invested in saving that person. Frequently, they can visualize their own spouse, parent, or child in place of the patient, and go all out to try to save them.

When these trauma activations are over, team members frequently do not have an opportunity to resolve their own emotional turmoil or achieve closure for the turmoil of the previous 30 minutes.

A recent paper from the Gunderson Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin, studied a practice that seeks to achieve this closure and recognize the life of the deceased patient. They call this the PAUSE, an acronym for Promoting Acknowledgment, Unity, and Sympathy at the End of life.

This process was implemented about five years ago, and a multidisciplinary team from a variety of religious backgrounds and beliefs carefully worded the script. It works like this:

- The team leader calls the time of death.

- Team leader then states, “At this time, we would like to take a moment to honor the patient and staff.”

- A chaplain takes over and does the following:

- (Chaplain states) For those who would like to stay,

we’ll take a moment of silence to acknowledge this

person, their death, and our care for them … - (Moment of silence—10 s)

- (Blessing)

We give thanks for ___(Name), those they loved, and

those who loved them.

We give thanks for the privilege of caring for them.

We give thanks for our caring team.

We ask that all may be whole and find peace. Amen. - (Chaplain states) Thank you for your care—for those

who would like to stay, please do, for those moving

on to other duties, Thank You.

- (Chaplain states) For those who would like to stay,

- The team disperses.

The research group circulated a pre-implementation questionnaire and then sent a post-implementation questionnaire two years later. The questionnaires were the same, except six additional questions regarding experience with PAUSE were added to the post-survey.

Here are the factoids:

- There were 466 participants in this study; the number of patients treated was not stated

- Participation rates were typical of questionnaire studies (40% pre-surveys and 23% post-surveys)

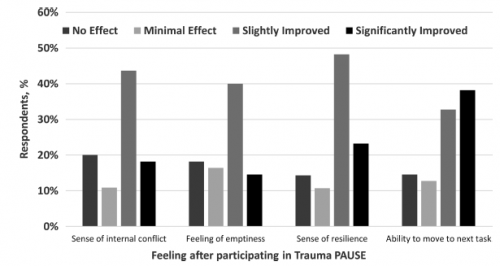

- While not statistically significant, many team members reported improvements in internal conflict, feelings of emptiness, resilience, and ability to move on to the next task

Note the higher slightly and significantly improved feelings in the post-study. This chart was based on 57 respondents.

The authors concluded that the PAUSE process was a meaningful way to help trauma team members emotionally.

Bottom line: Studies like this are difficult to conduct and even more challenging to apply rigorous statistical methods. They frequently do not have statistically significant results. But one can see specific improvements despite the soft numbers.

Many hospitals have some processes for terminal trauma activations. Most are not as well-scripted as this. But having been involved in them myself, I find it very helpful and comforting. I recommend all centers consider implementing something similar. Like most practice guidelines, this one is only suitable for adoption with adaptation. When adopting this, it is essential to work with your chaplains and recognize the specific ethnic and religious representation in your trauma center.

Reference: Trauma and Death in the Emergency Department: A Time to PAUSE (Promoting Acknowledgment, Unity, and Sympathy at the End of Life). J Trauma Nursing 29(6):291-297, 2022.