Over the last two posts, I’ve explored some of the current definitions of “life-threatening bleeding” and shared my own take on a simplified yet more universal definition. So how can we put this into practice?

In the trauma world, we typically need to use this definition when dealing with patients who are taking anticoagulants. When a patient on this class of drug arrives at your center after trauma, they must be evaluated promptly. This is frequently in the form of a trauma activation, which provides rapid access to labs and imaging. If the patient does not meet activation criteria, some type of expedited response (limited activation or rapid evaluation by emergency physician) is required. The most important decision that must be made is, “does this patient need to have their anticoagulant reversed?”

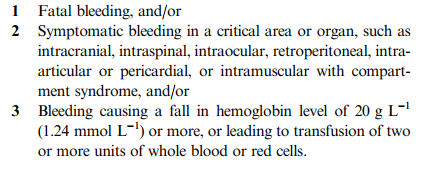

This decision depends on the answers to the two criteria I laid out in the last post. Is either of these present?

- (Physiologic) Bleeding that causes hemodynamic compromise (hemorrhagic shock) or changes in vital signs indicating progression toward it (increasing pulse rate, decreasing blood pressure).

- (Anatomic) Bleeding into a body region or tissues that has a high likelihood of causing death, disability, or the need for operative intervention.

The first one is easy. Actual or developing hypovolemic shock should be obvious to any clinician managing the patient.

The second one is not necessarily as apparent. Although one may think that any intracranial blood may be life-threatening, sometimes it is not. What about a little subarachnoid hemorrhage? Or a tiny subdural in an area that typically does not progress?

So how to we determine if definition 2 is met? Phone a friend. Call an expert. There are so many potential areas for this type of bleeding to occur, a single emergency physician or other clinician may not be able to accurately make this judgment. So call your friendly, neighborhood neurosurgeon (head), or surgeon (abdomen, soft tissues), GI specialist (UGI bleed), or obstetrician (baby stuff). If they agree that it is life-threatening, the reverse the anticoagulant.

This level of oversight is important, because the reversal agents are not totally benign, or cheap. They have known complications, and one rare but important one is death. So make sure that their use is justified.

Final tips: Once you have determined that reversal is required, use the fastest agent(s) available. For warfarin, this means prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) and not plasma. Typically, plasma reversal requires at least 4 units, and this takes hours. PCC takes 30 minutes or less.

Document your judgment well, and your conversations with specialists who are helping you with definition #2. This is critical, because there have to be checks and balances for use of your rapid reversal protocols. There must be a post hoc analysis of each and every reversal, just like there should be for use of your massive transfusion protocol. A group of knowledgeable clinicians must review the clinical information that was available at the time of presentation, and render their agreement or disagreement to provide a good feedback loop and ensure proper usage of these products.