The FDA announced approval of a blood test that incorporates both GFAP and UCH-L1. Approval was based on two as yet to be published studeis titled Evaluation of Biomarkers of Traumatic Brain Injury (ALERT-TBI) and Evaluation of Biomarkers of Traumatic Brain Injury Extension Study (ALERT-TBIx), and passed after less than 6 months of evaluation. Yes, more silly acronyms, I know.

The studies were designed to “evaluate the utility of the Banyan UCH-L1/GFAP Detection Assay as an aid in the evaluation of suspected traumatic brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale score 9-15) in conjunction with other clinical information within 12 hours of injury to assist in determining the need for a CT scan of the head.”

The former study started in 2012 and involved 2011 patients! The latter had only 119 patients, starting in 2015. Now, I have no access to their data, so I can’t tell what the FDA saw.

From Banyan Biomarkers’ website:

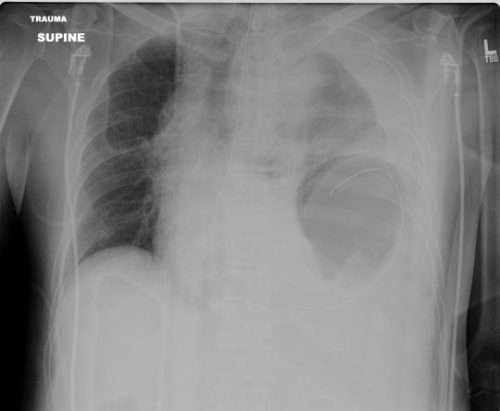

“The CT scan is widely available to assist clinicians in the evaluation of TBI, however, CT scans do not provide a clear and objective answer and scanning may increase the risk for radiation-induced cancer. Furthermore, over 90% of patients presenting to the emergency department with mild TBI, sometimes described as “concussion”, have a negative CT scan. Despite these limitations, nearly all patients are sent for a CT, which results in increased costs to the healthcare system and unnecessary patient exposure to radiation.”

Here are the (very) few factoids that I can find:

- CT scan results were compared to the Brain Trauma Indicator (BTI) blood test (GFAP + UCH-L1)

- BTI predicted a positive CT scan 98% of the time

- It predicted a negative CT scan 99.6% of the time

- Time to process the test is currently 4 hours

Bottom line: Sounds promising, right? Based on the data summarized over the last two days, I wouldn’t be too excited about this test, but the FDA was able to look at a study that I can’t. It appears that the negative predictive value is excellent, so I can see the application.

That being said, 4 hours is way to long. We can’t have a patient sitting in the ED waiting for the results to come back to decide whether they need a head CT. And how long will it take the assay to be widely available?

The devil will be in the details. What types of intracranial lesions were detected. Are the negative predictive values the same for subarachnoid, subdural, epidural, or intraparenchymal bleeds? And finally, how expensive will it be? How does the cost for the test compare to the cost of a CT scan done in 5 minutes?

I’ll let you know more as the details emerge. But don’t look for, or plan to use, this test at your hospital any time soon. There’s more work to do!

Reference: Banyan Biomarkers (banyanbio.com)