The 82nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma begins next week. As is my custom, I will be reviewing some of the more interesting (to me) oral presentation abstracts until the last day of the meeting.

When reading abstracts, keep in mind that you are seeing just a snippet of a finished manuscript. The authors are given very little print space to fully describe their research idea, their methods, and their results’ significance. Sometimes, what is seen in the abstract varies significantly from what is actually heard at the meeting. But mercifully, this does not happen often. The abstract is usually an intriguing look at some new and exciting work.

Having said all that, an abstract should not be a reason to change your practice! It is usually early work and needs to be fully vetted at peer review. Even then, it needs to be taken in context with past, similar research before trickling down to patient care.

The first abstract is fascinating. Our orthopedic surgery colleagues have been trying to use aspirin for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis for decades. Frequently, they are thwarted by the trauma surgeons, who are thoroughly indoctrinated in the low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) camp.

This work comes from the Shock Trauma Center in Baltimore and is a follow on to a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this year. The paper demonstrates that aspirin is not inferior to LMWH when used for VTE prophylaxis of patients. There was no difference in death from all causes, VTE occurrence, wound complications, or bleeding events.

The abstract is a follow-on to that manuscript. The authors performed a secondary analysis of the initial data to see if aspirin provided the same apparent level of protection in patients with high risk for VTE as measured by the Caprini score.

Here are the factoids:

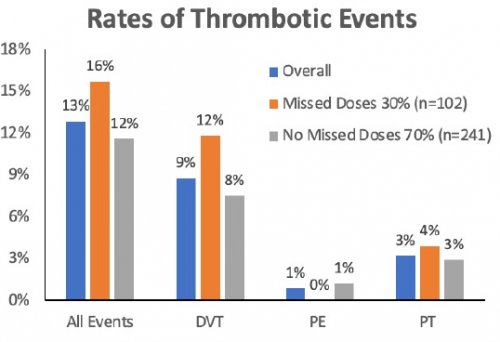

- A total of 12,211 patients were enrolled in this multi-center, and the same outcomes listed above were monitored for 90 days

- Of the total group, 3052 were judged to be high risk: 46% had a femur fracture, 42% had a pelvic/acetabular fracture, 48% had a thoracic injury, 39% had a spinal injury, and 35% had a head injury

- There was no difference in death, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or bleeding in the two groups

- Patient-reported satisfaction was significantly better by 68% in the aspirin group

The authors concluded that outcomes for aspirin vs. LMWH are similar, even in patients at high risk for VTE.

Bottom line: This is an intriguing abstract, pointing me to the original paper published in NEJM. This multi-center study was performed in conjunction with the research coordinating center at Johns Hopkins, which designs some top-notch research. This study was no exception.

I am fascinated with this work because it shows that our orthopedic colleagues were right! They’ve been trying to get us to use aspirin for a long time. It’s very cheap compared to LMWH, by a ratio of about 50,000:1.

If you’ve followed me for a long time, you would know I have been skeptical of the VTE prophylaxis establishment. Looking historically at its evolution over the last 40+ years, the incidence of DVT and fatal PE have changed very little despite the introduction of heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and anti Factor Xa monitoring. But it’s been established practice, so we’ve had to abide by the rules. Now, a cheaper alternative to all of this is being shown to be just as (in)effective.

I suspect that if others bear out this work, we will be able to use a cheaper prophylaxis drug that does not require injection. But we still need to work on figuring out the basis for this problem to hopefully reduce it to near zero someday.

References:

- Risk-stratified thromboprophylaxis effects of aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin in orthopaedic trauma patients. AAST 2023 Plenary Paper 3.

- Aspirin or Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin for Thromboprophylaxis after a Fracture. N Engl J Med 2023; 388:203-213.