In my last post, I discussed the growing number of choices for plasma replacement. Today I’ll look at some work that was done that tried to determine if any one of them is better than the others when used for the massive transfusion protocol (MTP).

As noted last time, fresh frozen plasma (frozen within 8 hours, FFP) and frozen plasma (frozen within 24 hours, FP) have a shelf life of 5 days once thawed. Liquid plasma (never frozen, LQP) is good for the 21 days after the original unit was donated, plus the same 5 days, for a total of 26 days.

LQP is not used at most US trauma centers. It is more commonly used in Europe, and a study there suggested that the use of thawed plasma increased short term mortality when compared to liquid plasma. To look at this phenomenon more closely, a group from UTHSC Houston and LSU measured hemostatic profiles on both types of plasma at varying times during their useful life.

All products were analyzed with thromboelastography (TEG) and thrombogram, and platelet count and microparticles, clotting factors, and natural coagulation inhibitors were measured. They chose 10 units of thawed FFP and 10 units of LQP, and assayed them every 5 days during their useful shelf life.

Here are the factoids:

- Platelet counts were much higher in day 0 LQP (75K) vs day 0 thawed plasma (7.5K). Even at end of shelf life, the LQP was 1.5x higher than thawed (15K vs 10K).

- Thrombogram showed that LQP had higher endogenous thrombin production until end of shelf life

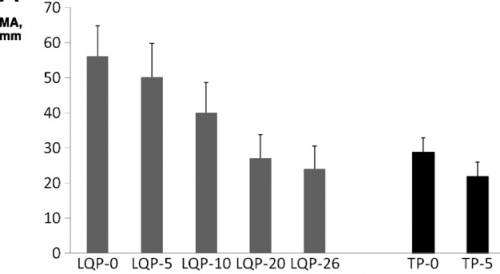

- TEG demonstrated that LQP had a higher capacity to clot that gradually declined over time. It became similar to thawed plasma at the end of its shelf life.

(TEG MA for liquid (LQP) and thawed (TP) plasma

(TEG MA for liquid (LQP) and thawed (TP) plasma - Most clotting factors remained stable in LQP, with the exception of Factors V and VIII, which slowly declined

Bottom line: Liquid plasma sounds like good stuff, right? Although there are a few flaws in the collection aspect of this study, it gives good evidence that never frozen plasma has better coagulation properties when compared to thawed plasma. Will this translate into better survival when used in the MTP for trauma? One would think so, but you never really know until you try it. Our hospital blood bank infrastructure isn’t prepared to handle this product yet, for the most part. What we really need is a study that shows the survival advantage when using liquid plasma compared to thawed. But don’t hold your breath. It will take a large number of patients and some fancy statistical analysis to demonstrate this. I think we’ll have to look to our military colleagues to pull this one off!

Reference: Better hemostatic profiles of never-frozen liquid plasma compared with thawed fresh frozen plasma. J Trauma 74(1):84-91, 2013.